HONORING OUR HERITAGE

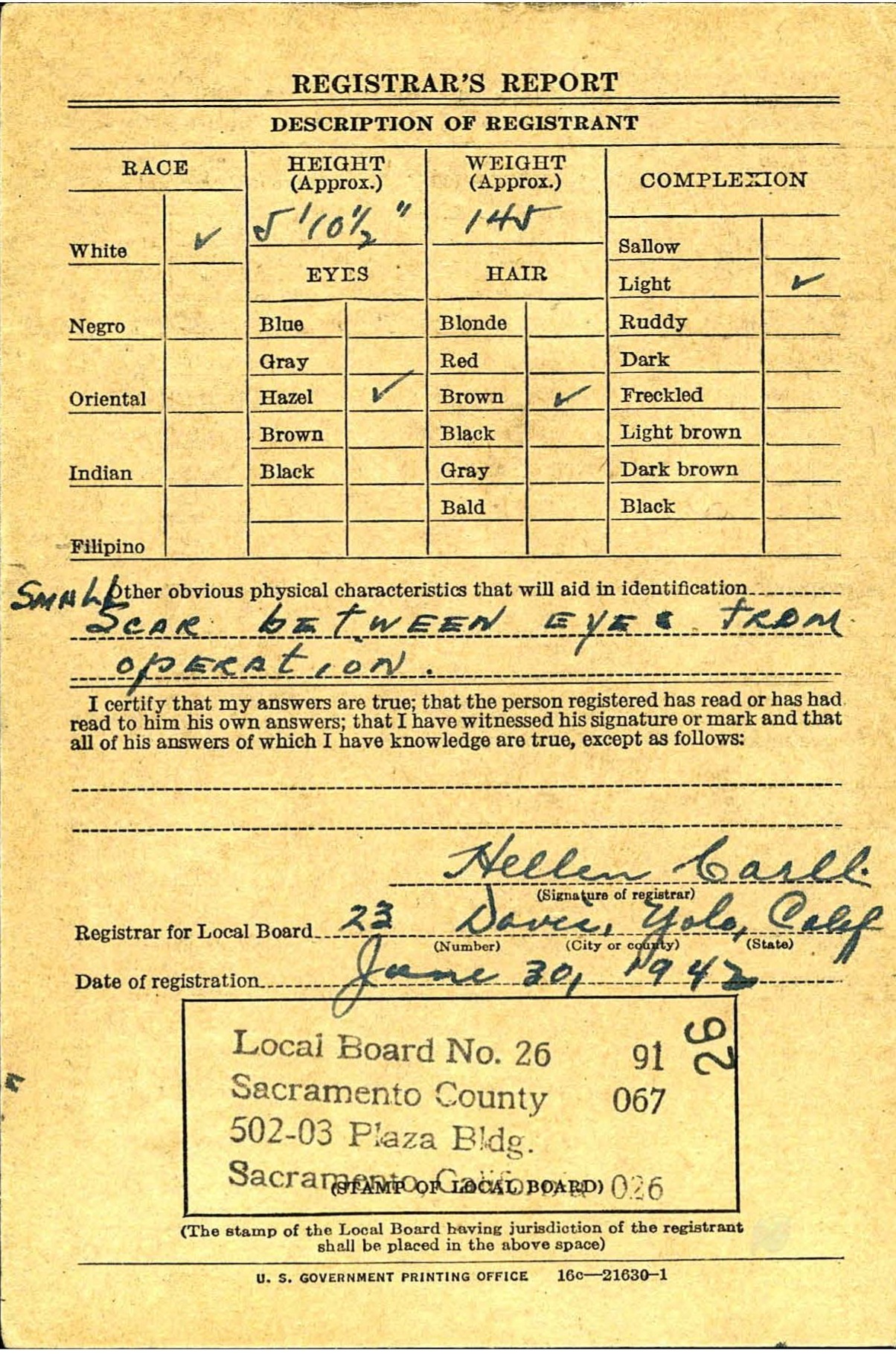

10th Mountain Division Soldier's Letter Home

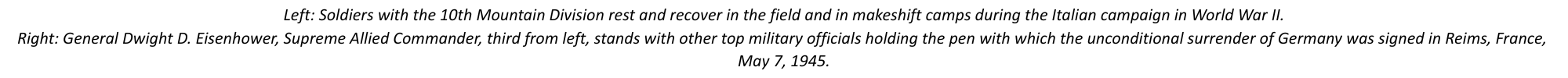

The 10th Mountain Division cemented its reputation as the Army’s premier alpine force, overcoming formidable German resistance in Italy’s Apennine Mountains and advancing through the Po Valley to Lake Garda in the closing months of World War II.

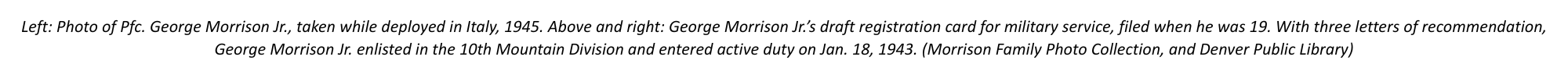

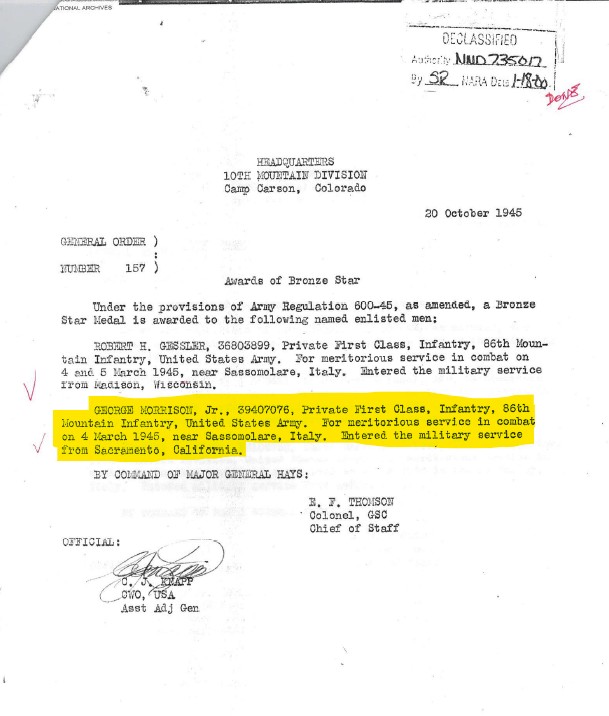

After enduring the hardships of war, Pfc. George Morrison Jr., a Soldier with Company C, 86th Mountain Infantry Regiment, 10th Mountain Division, wrote home to his parents on June 27, 1945, capturing his experiences in a letter.

Dear Mom + Dad, June 27, 1945

I have a little time this afternoon, so I will write a little of all the things that I have done in the past several months. I had gotten out of the hospital November 23, 1944 and had a week on pass in Austin. I went in Saturday and met a family who gave me a ride in their car and took me to their parents’ house for a meal. They asked me to come for Thanksgiving dinner a week after the nation had it, but Tuesday I was sent back to the company.

I phoned Aunt Alice and you all telling I was leaving Swift. On Wednesday evening we were taken by trucks to the train in Camp Swift. Thursday we went through Oklahoma, then Kansas, Missouri hit Saint Louis at midnight, then Illinois, (cold snow on ground) Indiana we got out for 30 minutes and ran around in the snow. It was very cold, glad to get back in the train. We continued Ohio came into Cincinnati Friday night about 8 PM then on to West Virginia to Camp Patrick Henry.

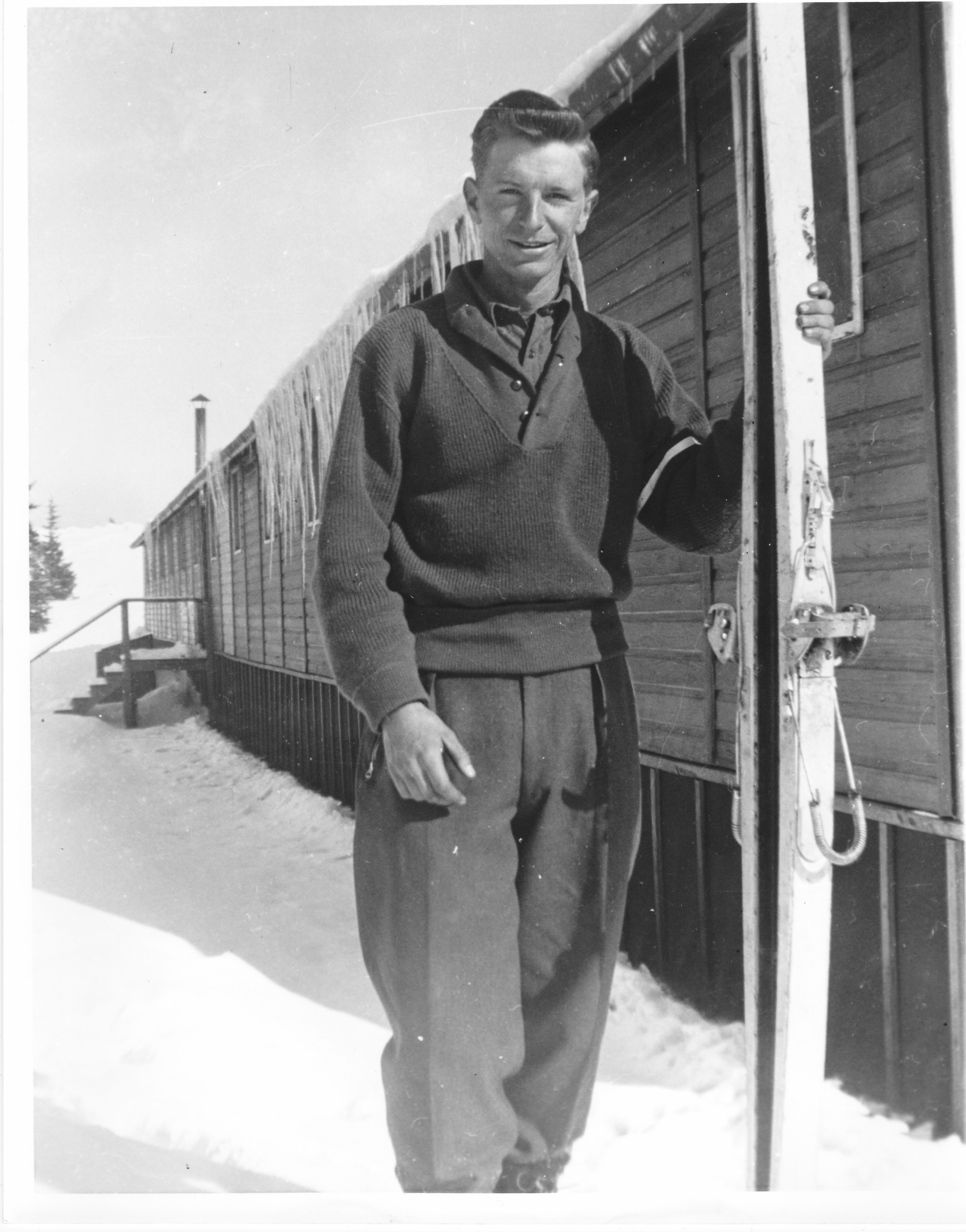

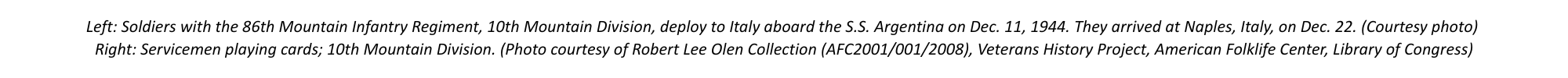

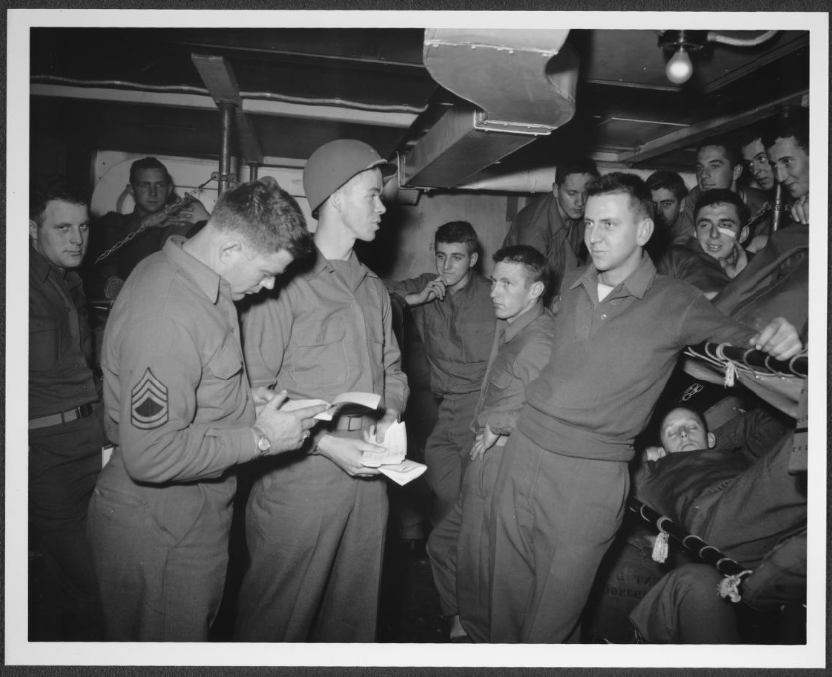

It’s about Newport News, Virginia where we stayed three days. It was cold there and a little damp. I got all new clothes and checked equipment. Phoned you all a couple of times. Then Saturday night at 11 o’clock we walked to the train which rode us 20 miles to the boat at Newport News. I was given a dixie cup of coffee by the Red Cross, (another) and stepped on the gang plank about midnight. I went down to the D deck, just above the water line. The boat was loaded and started out at 8 AM Sunday December 10, 1944 we met part of a convoy that noon and later at night. I was on a boat called the Argentina. It was an Eastern Boat Lines to South America before the war.

We were really crammed into the holds and I had a fellow sleeping above me and three under. Some were 8 men high, but we managed.

I slept next to Jack a teacher from north Sacramento, teached at Grant Union. We are good friends.

I was free all the time and walked around the deck every day and almost every night. We ate a fair chow and I even got a little sea sick but got over it in a few days. We had had calm weather all of the trip but the waves were a little rough.

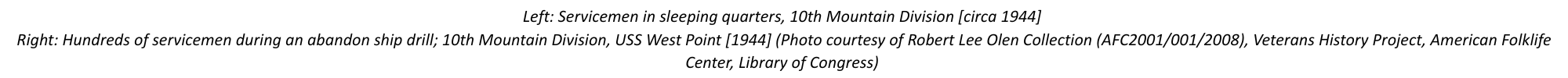

The 10th day we sighted land. Africa! We went through the Straits of Gibraltar and I was taking it all in. The weather was bad when we were in the Mediterranean near Algiers. I looked over the funny African countryside. The 13th night, December 22 we pulled into Naples Harbor about 9 o’clock. The weather was cold, windy and damp.

The next morning we were pulled in and I looked over Naples from the boat. You could see the damage which was done by us by air and artillery. We got off the boat December 23 about noon and a Red Cross girl gave me 2 doughnuts, (coffee in the states doughnuts here). We were driven through Naples to a large modern school which used to be the Italian West Point. Of course, it was airy, no windows because for our bombs and cold, no heat. We had C rations in cans and slept on marble floors. I had a lot of blankets. I went to the Red Cross where it was warm, ice cream after sweating out a long line. I wrote you all a couple of V- mails.

I met Lee Gebhart and talked to each other. The most of the day, December 24 I spent at the Red Cross and just sitting and writing. I went there Christmas Eve (night) too. We had to go back to the school and to bed by matches.

December 25, Christmas Day, we had a dinner, and had turkey then got ready to leave at noon. We boarded train in Naples Christmas noon. It was cold and the train was just box cars but about half the size of our box cars at home. We had 25 men per car, it was crammed, but it was cold and everything was o.k. We even opened up the sides so we could look out. The car rode like a bucking horse, but I slept and did ok. I woke up when we passed Cassino, so I saw the rocks and rubble which was once a town. We went up to the outskirts of Rome only a mile away, we continued up to a station about 35 miles from Livorno (or Leghorn) then we got on trucks and rode up to Pisa. We bivouacked outside of Pisa about three miles. I could see the leaning tower.

I had a little pup tent with another fellow and there we got our equipment and stuff that we needed. It was cold there and a heavy frost. We could see snow all over the mountains and hear artillery fire. We were put on the alert because they were having trouble up on the bigger front. They dumped out ammo to us and we got everything we needed. I had to dig my first fox hole in case we were attacked by aircraft. We did have an alarm, but some were just caused by a false thing. We spent three days there then moved back by trucks to below Leghorn about 10 miles. We bivouacked on hills overlooking the sea. I spent New Year’s Eve and a few days there.

Because my knee was not in good shape and they wanted to give it time to heal, they let me guard duffel bags for a couple of weeks near Pisa. About 10 miles outside of Pisa.

I was sent for about February 3 and from there I went up front to San Marcello. We left there in two days to go back to Lucca. We rested in some large estate about 9 miles outside of Lucca until February 16. We packed up and got on trucks for the front. We got off at Vidiciatico and hiked about 12 miles to within yards of the German lines. We had a hard time finding the buildings and I was falling and slipping on the ice and snow but somehow after getting lost, I caught up with a couple of fellows and we made it to an old stone house. The company was in these two houses the few hours of the morning Feb 18 and left at dark for the attack up to Riva Ridge. It was cold and I helped carry signal wire up a ways and keep the line open to the company going up. I went back to the house where I helped with 1st Sgt. Shaffer stay on the phone both day and night. I took the messages to Battalion one night through enemy territory and I had that rifle ready to kill if I saw a shadow move. I had to go through snow over a hill and through deserted villages and with the moonlight every tree made a shadow look like a person and enemy. I got a couple of hours rest then took over the phone.

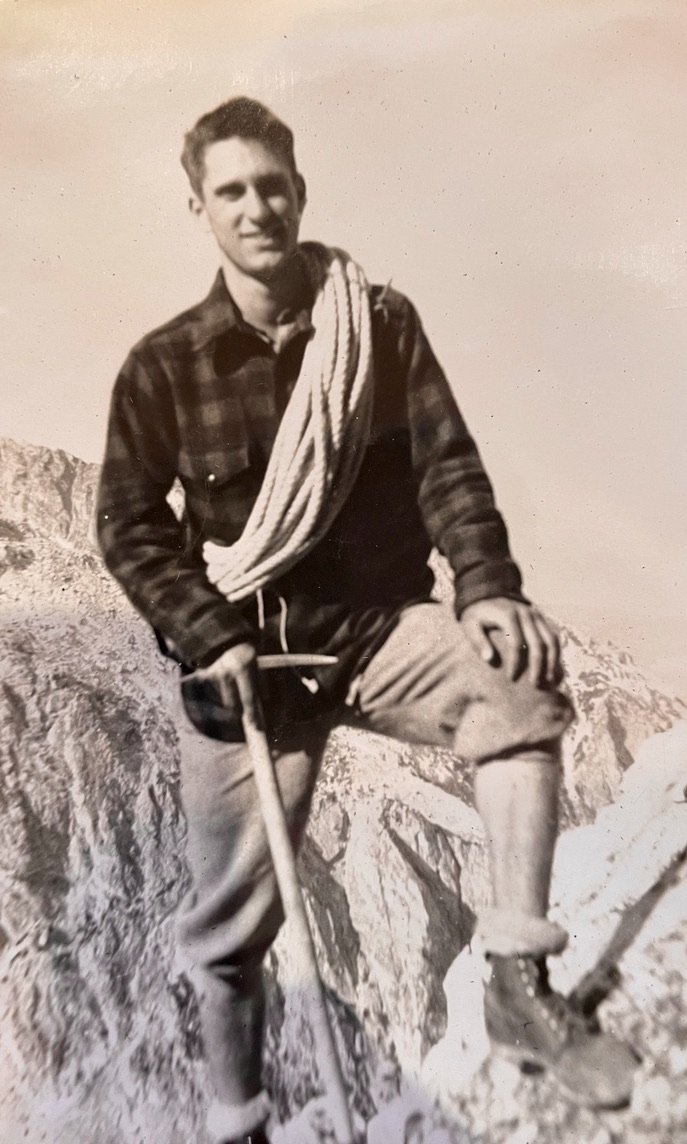

When I was on I had to call Battalion and report they reached the ridge and made it ok. The next day they had a fire fight. I reported some artillery which came in near us. That night of the 19th of February the weather was cold and I was talking to a Lieutenant friend who was up on the ridge. At 2 AM of the 20th, he went out because of a patrol (Germans) was attacking them again on the right flank. He was killed with about 10 other friends of mine. 3 fellows were captured. I heard a couple of days ago that one fellow who was captured got home.

I helped haul down the wounded. I worked five hours on this one good friend of mine, it took him 15 hours to get down from the top. It was a hell of a trail. I helped give blood plasma. Other friends of mine who was shot through the neck and chest, others the legs, ankles and others had to lose their feet or legs because of the cold and it took so long to get down.

The 21st of February we moved back to a little town and took off for Gaggio Montano. Rested 2 days and the third day took a short truck ride for about five miles outside of Gaggio Montano. (A little artillery came in while we were on the rest and I even slept through our own artillery.) We hiked up to almost the top of a hill and dug in good deep fox holes. I and the 1st Sgt. slept together. We waited 2 days there and pushed off March 3. We attacked for about five miles and then hiked to an area up a ways and dug in. It was midnight. During the night they (the Germans) threw in some artillery close and with the cold weather and artillery I was shaking and freezing. We had C rations the next morning. I helped carry a case to the company, just so I could eat it.

We got ready after eating dog biscuits and went into the march for a ways before the attack. We had a 15 minute or longer artillery barrage on the town while we were walking up. I would keep my eyes on the fighter planes while they strafed the town bombed it with gasoline bombs. The artillery lifted and then we opened up with machine guns of our own. The enemy let the company get almost to the town which was up on a hill and then they opened up with machine guns and mortars. I started to dig in then I moved so much that I forgot about digging in. Their mortars were getting close and I hoped they would be put out. I fired at a German who was directing the mortar fire, but I don't know if I hit him. The tanks came up and that helped out more than anyone will ever know. We started to continue up to the town, even when a German tank opened up on us. Our tanks knocked them out.

Because the company was shot up pretty bad, I went up and helped out with a BAR man in the assault platoon for the next attack up the next mountain. The artillery and mortar fire was coming in thick and heavy. We had an hour rest and it seemed like a life time. We pushed off at 1 PM and then over the top we went. I was running back and forth and forward hitting the ground in defilade and ditches and firing at different German dug outs. We were being fired at but you had to advance.

We were doing ok when we got down in the valley we had to wait until our flank caught up. They were nowhere in sight. We were pinned down while our artillery put in a barrage over our head on to a level spot a few yards over us. I can't explain myself, it is a wonder I am not gray haired now. It lasted for a 1/2 hour, but God must have been with me. The men killed (were) behind me, but anyway we continued and I saw a German and fired at him, others did also. I think he was killed. We reached the top and dug in. That night we took guard post and I watched miles of German land. The next morning a German patrol came up and a man killed the German captain by cutting his head off at the forehead with a BAR.

A friend and I dug in on the forward slope under sniper fire. We sweated out from March 5 till 16th then we had to walk back through Purple Heart Valley to where we got trucks went to Montecatini on a battalion rest. My nerves were shot because of all the artillery and mortar fire at us those 14 days. I saw three movies and had a couple of cups of coffee and cookies at the Red Cross.

I went back on line the 20th of March and stayed 2 weeks. We had three more days rest then back to the front. We waited around there until April 15 and you should have seen the tanks, halftracks, artillery and everything. It looked like a great circus. The push off came in the morning after about 45 minutes of artillery bombing and all fires possible. It was hard the first day, the mines fields hurt and killed a lot of fellows, but the push went on. The first night they went a good ways and the second day they were looking over the Po Valley. Spent next day in Po and artillery fire was coming in.

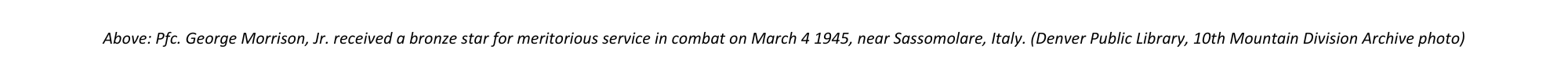

April 23, at San Benedetto, crossed the Po river. We had been drinking champagne and wine till everyone was almost drunk.

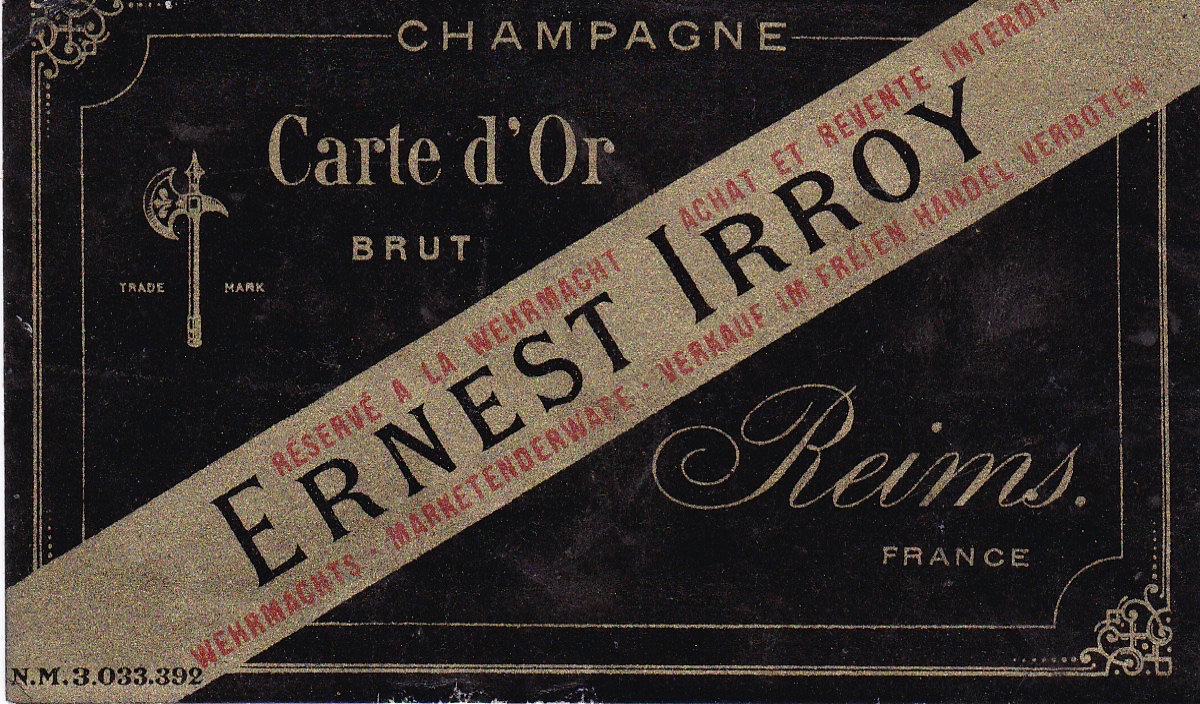

The attack went on, fast and couldn't stop us. It did take about six days to reach the mountain overlooking the Po Valley though. We crossed the river. I went up to Bussolengo, spent the night in a town and had some more wine, ate bread and a couple of fried eggs. We went up to Lake Garda and the 86th had a hard time going up to the north part of the lake. The Germans had everything ready. I went up to the end of the lake in a duck and brought up the mail I had. We stayed there and didn't attack and a day or two later we found out the war was over. It rained a lot and it was cold and damp. Were afraid to build fires or have lights for fear the Germans would shell us, but I guess the war was over for us here in Italy. I was so glad that I went in bed and didn't worry much about artillery fire. Fellows fired their rifles and pistols, but I just went to bed, May 2, 1945.

The rest of the war ended May 7 and 8 and during my time up on Lake Garda, I went swimming and over to this little town across the lake. I slept at a little hotel and we bought some fish from a fisherman and had them prepared by the little hotel family. We had wine and sat out on the porch looking over the lake, which was a beautiful sight like Lake Tahoe.

We moved back by truck to Brescia, and bivouacked on an Italian airfield for a few days. It was hot there and I went in one night to Brescia and looked over the town with a fellow from Sacramento called Bino Grifantini. We had some wine then back to bed at 10 o’clock.

I went the next night down to where the German Armies were going into the PW cage. We heard the papers say Tito wanted Trieste and they didn't want him to have it.

We were sent up to make sure the mountains and roads were kept open up here at the Austrian, Yugoslavian border.

We are here resting, rock climbing and going on passes. I hope to go on one to Trieste shortly. I will write about it.

We are waiting to see what is in the future, but I am resting and taking life easy. I will close for now and write any news later.

Always love,

Brother

The Story Behind The Letter

Saturday – 9 Dec 1944 at 11 p.m. – Troops walked to a train that took them about 20 miles to Newport News, VA

Sunday – 10 Dec 1944 at 12 a.m. – The 86th boarded the SS Argentina

“Every man was busy with his equipment. It was a (big) job to handle the overloaded pack and duffle bag that each man carried, to say nothing of the rifle, gas mask, and steel helmet.”

Saturday – 23 Dec 1944 – The Argentina is pulled into port and the 86th puts boots on the ground in a war zone

“Bagnoli was a staging area, and the regiment was not to remain there long, for which most of the men were grateful. The marble floors they slept on were cold, and the rations were infinitesimal.”

Monday/Christmas – 25 Dec 1944 – 1st Battalion leaves with advance party by train at noon, Morrison mentions how packed the trains were and having to finish the trip by truck, but did not tell his parents about the train wreck they had survived on the way.

Wednesday - 27 Dec 1944 – Sunday - 31 Dec 1944 – 1st Battalion bivouacked in staging area near Pisa, the Battle of Garfagnana was intensifying a short distance away.

Sunday - 31 Dec 1944 – 1st Battalion moved to bivouac in Quercianella

Saturday 3 Feb 1945 – Morrison is called to the front, joins 1st Battalion in San Marcello and then moves with the 86th Regiment to Lucca

Sunday - 18 Feb 1945 (Evening/Overnight) – B and C Companies start climbing Campiano Ridge. Morrison relays communications between his company and the battalion and helps bring down the wounded.

Tuesday - 20 Feb 1945 – In the early morning hours, not long after speaking with Morrison, 1st Lt., John McCown is killed in action as the fighting on Mt. Serrasiccia continues

Wednesday - 21 Feb 1945 – 1st Battalion is relieved by 10th Reconnaissance Troop and 10th Anti-tank Battalion and leaves the ridge, moving to Gaggio Montano

Friday – 23 Feb 45 – Gaggio Montano comes under enemy fire, but Morrison and others are so tired that they sleep through it

Saturday – 3 March 1945 – The next attack begins after dawn, with 1st Battalion to take the high ground east of Monteforte and Hill 928 – Objective Able, Morrison recalls in his letter that between the cold and the artillery, when he wasn’t moving, he was shaking and freezing

“The Rover Joe planes were out again, strafing possible enemy positions. Up on the ridge and down another the planes went, beating the ground with their machine gun fire. On the ridge running down from Mt. Grande, the 1st Battalion men sat on the edge of their foxholes and cheered the planes as they did their deadly work. Suddenly one plane headed directly for the 1st Battalion positions and dived low, continuing its fire. The men below sat stunned for a moment and then leaped for cover. Some didn’t make it. The pilot, confused by the sight of similar ridges below him, had misjudged his terrain.”

Tuesday – 17 April 1945 - The 1st Battalion advanced to la Palazzina, then moved to the high ground

Thursday – 19 April 1945 – The entire regiment was rested as much as possible to prepare for an all-out push into the Po Valley. Many of the men had little rest however; as the Germans continued to rain mortar and artillery fire on the rear areas

Friday - 20 April 1945 – The 1st Battalion moved into the valley at noon; the advance was going like wildfire

Sunday - 22 April 1945 – 1st Battalion encounters fierce enemy resistance

“At 2045 (8:45 p.m.) the armored elements joined the waiting infantry, and the thrust toward Verona began. By 2330 (11:30 p.m.) the regiment was in striking distance of the city. Civilians reported that there were no organized combat units in the city and that most permanent garrison personnel had been evacuated.”