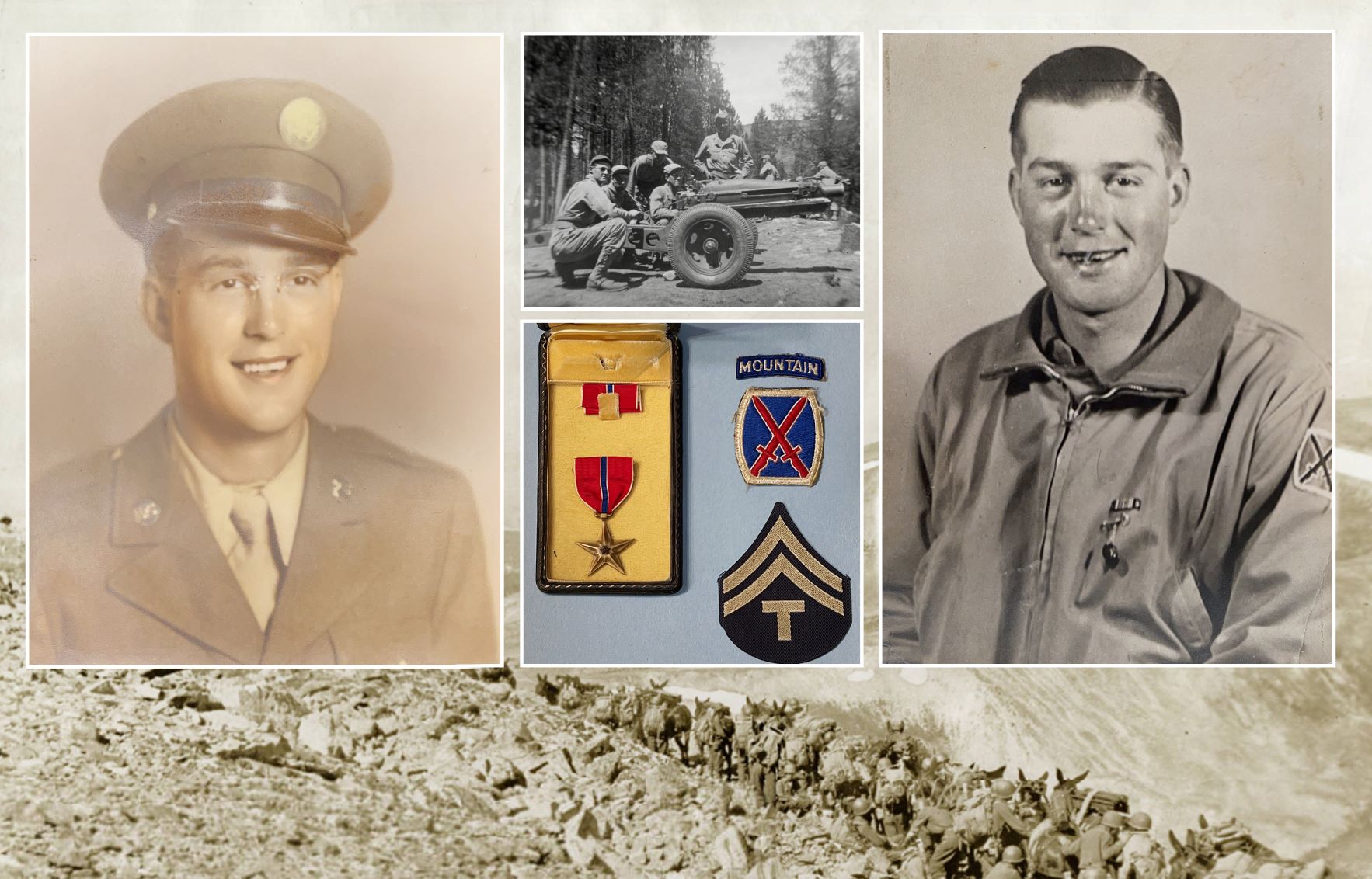

Pfc. Earl Siebert, assigned to A Battery, 605th Field Artillery Battalion, 10th Mountain Division, received the Bronze Star for his actions during the Po Valley campaign in Italy during World War II. He recently celebrated his 97th birthday. (Photos courtesy of the Siebert Family)

WWII veteran recalls serving with historic 10th Mountain Division

Mike Strasser

Fort Drum Garrison Public Affairs

FORT DRUM, N.Y. (Dec. 15, 2021) – For decades, Earl Siebert never spoke about serving with the 10th Mountain Division during World War II.

Although his favorite television programs were about the military, he remained tight-lipped about sharing any of his own experiences in the Army. It wasn’t until two of his grandsons became commissioned officers that he began mentioning it at all.

One of his grandsons, Maj. Malcolm Wilson III, said he was headed to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, in 2007 to complete the second phase of Basic Officer Leadership Course.

“This was the first time Grandpa mentioned his service to me,” Wilson said. “He said that he was also stationed there for a time to receive some field artillery training.”

In 2015, Wilson was assigned to the U.S. Army Sustainment Command at Rock Island Arsenal, and he led a team to Europe to conduct site surveys. While there, he was able to visit a World War II museum in Belgium. Later, he showed photos of his trip to his grandparents – one of which was a 75 mm howitzer that was made at Rock Island Arsenal.

“It was almost as if it uncorked a bottle,” Wilson said. “Grandpa immediately recognized the artillery piece and stated that was what he was assigned and trained to use during his time in service. This led to several stories about his service in Italy.”

Today, surrounded by family during the holidays, he is inclined to share an Army story or two when asked.

“When I was growing up, my father would not talk about the Army at all,” said Earlene Siebert, his daughter. “He will talk about it now if anyone asks him about it.”

Siebert was raised on a farm in Midland County, Michigan, and he grew up knowing the value of a hard day’s work. He wasn’t much older than 10 when he joined his father to plow fields with a team of horses. If something broke off the plow, Siebert would run back home to get a spare part. Once, he was driving a tractor down a steep, bumpy hill, and the hay wagon came loose and nearly crushed him.

After finishing the eighth grade, Siebert stayed home to farm with his father. The work left little time for hobbies or pastimes, but he was given a harmonica and he learned to play it by ear.

At age 20, Siebert had no intentions of enlisting in the military when the U.S. entered World War II. His mother developed a bad case of tuberculosis and one of his younger sisters was stricken with polio, so Siebert’s priorities were taking care of his loved ones and the family farm.

However, the draft had other plans for him, and he received orders for basic training at Fort Sill, Oklahoma.

“I didn’t want to enlist, but they were drafting people and I ended up going anyway,” Siebert said. “I expected I would have to go.”

Siebert was assigned to A Battery, 605th Field Artillery Battalion, 10th Mountain Division, and he went to Camp Swift, Texas, for field artillery training. He became proficient on firing the 75 mm howitzer, and he learned how to disassemble it and then pack the pieces on mules.

Mules were capable of carrying heavy loads over different terrain. Siebert recalled how it took four or five mules to transport one 75 mm howitzer.

“We could put the barrel on one mule, and on another we had one wheel on each side of the saddle,” he said. “But we never used them overseas.”

Siebert said that sometimes the mules would be frightened by loud noises and then run away with parts of their howitzer. Soldiers would eventually hook the howitzer onto military trucks instead of mules to move them.

“Where we went over in Italy, the terrain was pretty good for hauling the guns on the back of trucks,” he said. “So that was the way we went.”

Siebert said they also had to deal with artillery guns that were prone to breaking apart.

“Firing it wasn’t bad at all,” he said. “But the 75 howitzer was a pretty delicate piece of equipment. You wouldn’t dare follow one of those vehicles that had one in the back because it was that simple to damage it in some way, like the wheels coming off on it. It wasn’t always built right, but we used them anyway.”

By July of 1944, units of the 10th Mountain Division arrived at Camp Swift from Camp Carson and Camp Hale, in Colorado. While acclimating to the Texas heat, Soldiers continued infantry training with regular foot marches that ranged from 10 to 25 miles.

Three artillery units – the 604th, 605th and 616th Field Artillery battalions – were under the command of Brig. Gen. David L. Ruffner. Maj. Gen. George P. Hays would take command of the division on Nov. 23, 1944.

Siebert and the 605th Field Artillery Battalion embarked on the USAT General Meigs just after New Year’s in 1945, arriving in Naples on Jan. 18.

“There was a big dock and we could see some of the boats sunk right there in the harbor,” he said. “From there, we went on our LCIs (Landing Craft Infantry), which were about 100 feet long.”

The LCI was a class of assault ships used in WWII to land large numbers of troops onto shore. Soldiers could feel every wave off the steel-plated flat-bottom hulls, which resulted in sea sickness.

“We had a convoy going up the coastline, and I remember the weather being nasty,” Siebert said. “It was so rough on the LCIs, going up and down. There were people getting sick and they would have to heave up – it was an awful experience.”

This was his first time on a ship heading to a foreign country. When he landed, Siebert remembers seeing an Italian man sitting on the pier and catching fish.

The Soldiers watching the man were stunned to see him bite into the flesh of the live fish and then take a bite of bread from his pocket.

“That’s what I call hard living,” Siebert said.

The 10th Mountain Division’s field artillery units contributed to the attack on Riva Ridge and Mount Belvedere, blasting enemy fortifications from the valleys below. To maintain the element of surprise, they were ordered not to open fire until the infantry had reached their objective.

Siebert endured several months of fighting and earned the Bronze Star for his actions near Torbole, during the Po Valley campaign. The division suffered 506 casualties to accomplish this mission, including 91 killed in action.

“His military experience was not pleasant, and until recently he never told us how many of his friends didn’t make it back home,” Earlene Siebert said.

Wilson said that when he asked his grandfather about the Bronze Star, he credited others over his own actions.

“It is a bit humorous to hear him describe how his own efforts were not that impactful, but everyone around him did all the work,” Wilson said. “He is fairly humble, and just doesn’t want to be recognized for anything. He believes he was just doing his job.”

His award citation, dated June 17, 1945, stated:

“Using howitzers for the first time as assault weapons, Private First Class Siebert participated in an amphibious landing in support of a mountain infantry regiment in its attack on the enemy. Displaying great intrepidity, he helped wheel the weapons out on a road, under direct enemy observation at all times, and directly fired at targets of opportunity, and at targets called back by the foot soldiers.”

Firing and then advancing down the road several times, the artillery batteries were subjected to constant counter-fire throughout the day until they ultimately stifled enemy resistance. The citation concluded:

“His great courage, teamwork and daring are exemplary and do much to uphold the highest traditions of the United States Army.”

Siebert doesn’t dwell on the battles or campaigns during the war.

“It was a good experience anyway,” he said. “For as long as you aren’t getting shot at. But we had that experience too. We’d set up our guns and when you hear that noise overhead, you knew damn well that they were shooting back at you. And they would be shooting into the little town behind us, and we’d hear those doggone whistling shells coming in.”

“I’ll tell you, well, I’m getting too old to really remember some of that stuff,” he added. “But I’m sure glad I was in an artillery battalion. We were pretty well safe from much of the counter-battery fire. We weren’t getting the direct fire like the infantry.”

Siebert also remembers what American air superiority looked like during the war.

“I had never seen so many bombers flying overhead in my life,” he said. “They were flying over Brenner Pass, bombing the Germans who were trying to get back into Germany, or out of Italy, anyway. It was something to see – drove after drove of them.”

Toward the end of the Italian campaign, Siebert had the opportunity to see more of the country.

“We would travel on our trucks, and I can remember the Italians would hand over big bottles of wine to each one of us,” he said. “The war was won by then, so we had a good time.”

When the war in Europe officially ended, Siebert returned home on furlough, but it was almost certain that his unit would be sent to Japan.

He was sitting in a movie theater when the film was interrupted with an announcement that an atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. On Aug. 15, 1945, President Truman announced the unconditional surrender of Japan. Siebert would not be returning to overseas duty after all. The 10th Mountain Division was inactivated three months later.

“I got out of the Army after that,” he said. “I just wanted to go back to farming.”

Siebert eventually went to work for Dow Chemical in Midland, Michigan, where he performed maintenance work on the company’s first railroad. He married his wife, Rosemary, in July 1948. Together they raised three daughters, and they were blessed with eight grandchildren and 14 great grandchildren.

Siebert recently celebrated his 97th birthday; his wife turns 95 this month. He said that they remain in good spirits with a regimen of healthy eating and prayer.

“You’ve got to conquer life somehow,” he said.