*This article was edited with the assistance of artificial intelligence (AI) tools. Final review and editing were conducted by authorized DoW personnel to ensure accuracy, clarity, and compliance with DoW policies and guidance.

*The contents of this article do not represent the official views of, nor are they endorsed by, the U.S. Army, the Department of War, or the U.S. government.

![]()

Published 2/5/2026

By Major Joshua Tosi

During Warfighter Exercise (WFX) 25-3, the 42nd Infantry Division (ID) protection cell became consumed by immediate threats—a common pitfall known as the “current fight.” This reactive posture, driven by the need to address emerging threats, hindered effective future operations (FUOPs) planning and limited the cell’s ability to anticipate and mitigate risks. Army doctrine publication (ADP) 3-37 underscores that protection is not merely a reactive task; it is a continuous process integrated across all aspects of military operations.1 The cell’s initial 24-hour focus, reflected in its protection prioritization list (PPL) illustrates the extent of this reactive posture.

To address this issue, the division adopted a 96-hour, tiered protection planning schedule. This change required a proactive mindset and deeper integration with other operational elements. The protection cell had to insert itself into key planning events—rather than waiting to be invited—most notably the Targeting Working Group (TWG). This integration enabled the protection team to contribute to the targeting process by nominating targets aligned with defensive priorities, including space-related vulnerabilities and Information Operations (IO). It also highlighted how offensive actions, such as artillery fires, could reinforce the overall protection plan.

Similarly, the Protection Working Group (PWG) should contribute to targeting by identifying protection-driven nominations—particularly space-based and IO-related—and by articulating how fires can reinforce protection objectives. Equally important, deeper coordination with the G-35 (FUOPs) section ensured that protection considerations were incorporated into the division's operational plan from the outset. The PPL development process must both inform and be informed by this plan, embedding protection effects early in the planning cycle.

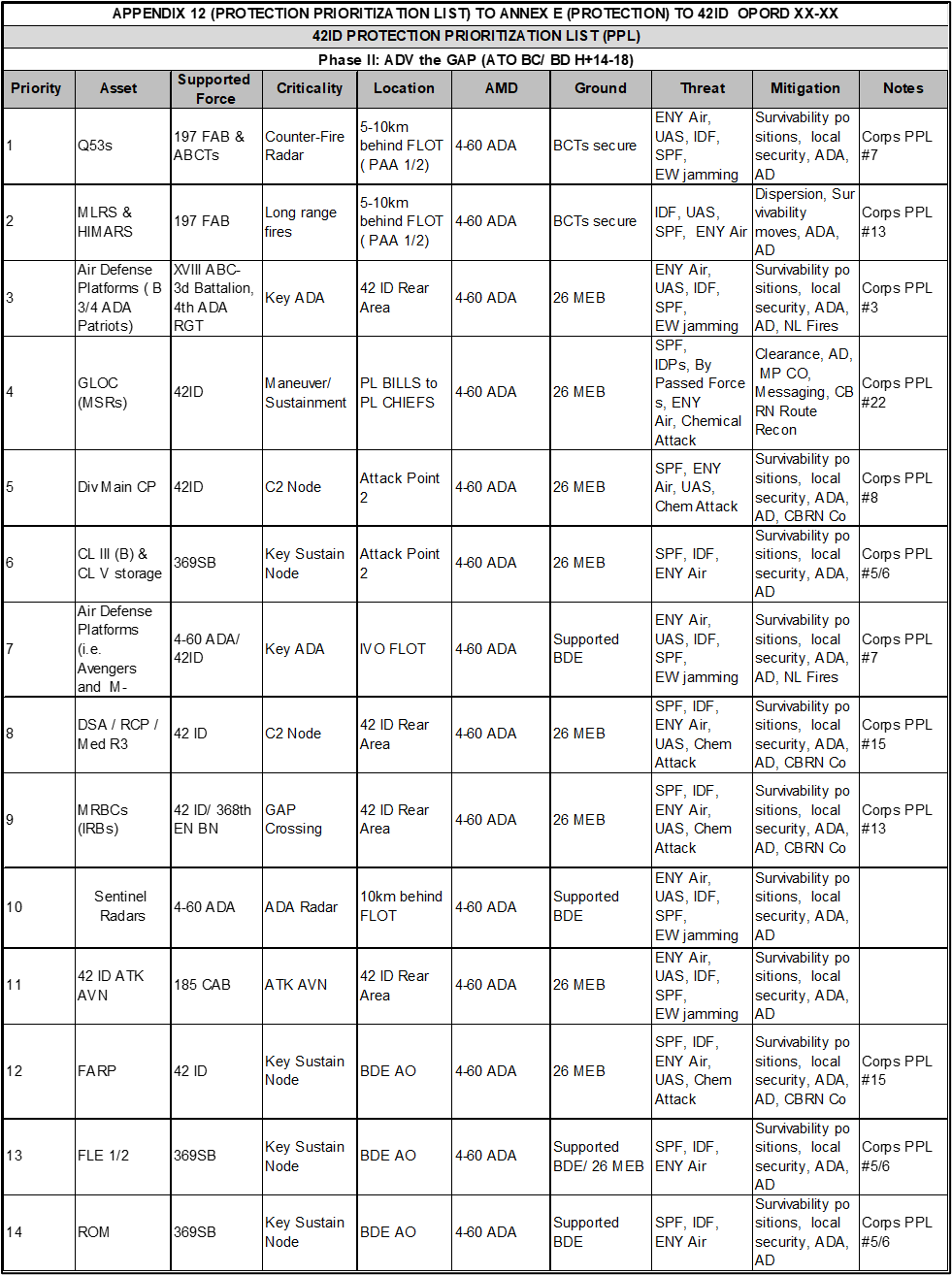

The PPL serves as the primary planning document for identifying and resourcing protection requirements. The 42nd ID initially used a PPL format that ranked critical assets numerically, with “1” representing the most important (see Figure 1). Although this approach drew on assessment data, it did not give commanders a clear understanding of asset criticality or the rationale for prioritizing protection resources.

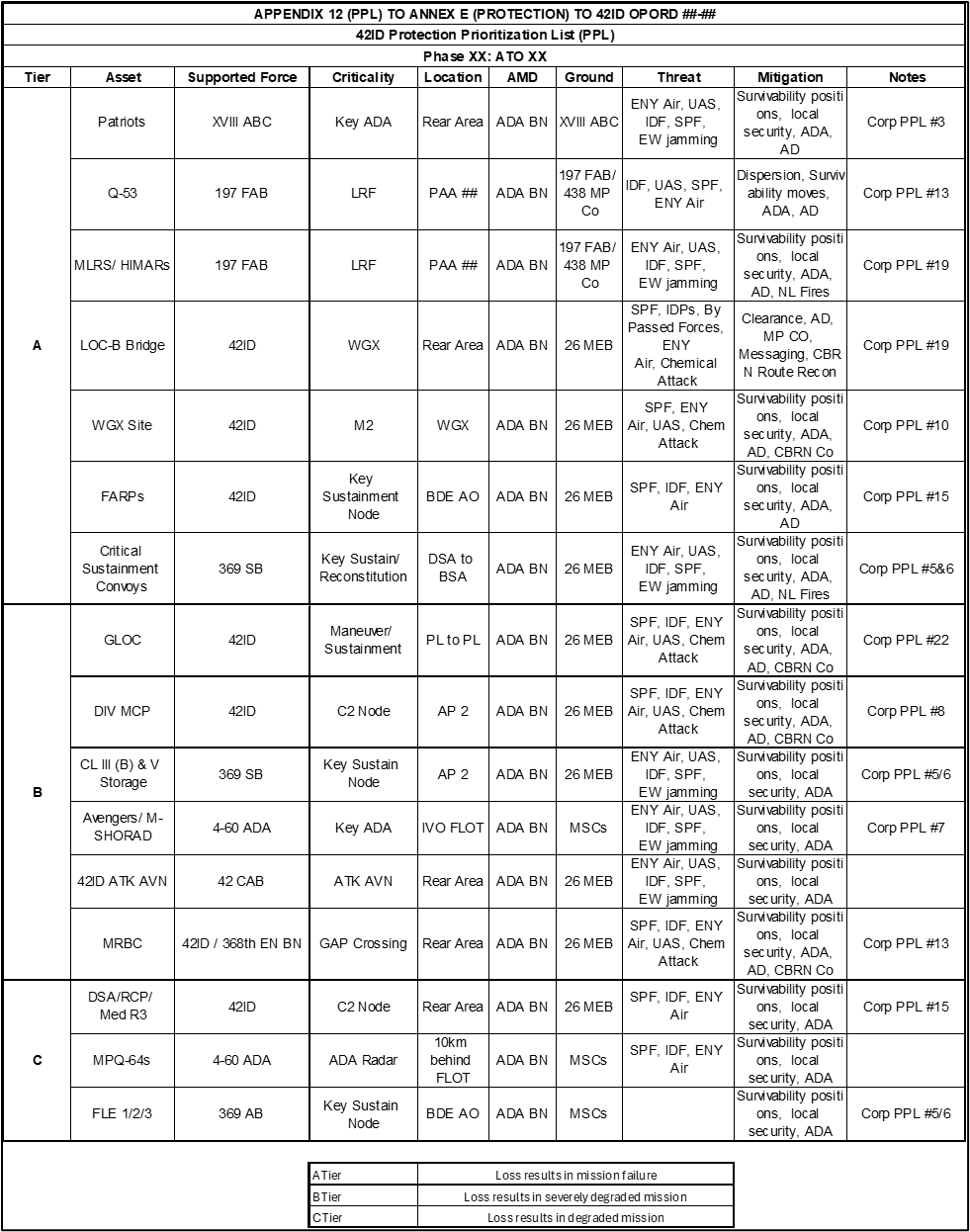

By mid-exercise, the division transitioned to a more flexible, tiered PPL system (see Figure2). This method grouped assets into tiers (A, B, and C) based on their relevance to a specific operation. Assets within a tier were not ranked against one another, giving planners the agility to shift focus as conditions changed. For example, the multirole bridging companies (MRBCs) initially fell into a lower tier (C-Tier) because they were not required early in the operation. However, as the division prepared for the wet-gap crossing, the MRBCs became essential to mission success and were elevated to the A-Tier—signifying that their loss would result in mission failure.

Figure 1: 42nd Infantry Divisions Initial PPL

The PWG is central to the division’s protection planning. However, WFX 25-3 revealed that its initial focus on current and near-term operations—the next 24 hours—was unsustainable and undermined proactive protection. This reactive posture ran counter to the guidance in ADP 3-37, which stresses the importance of anticipatory measures, noting that “protection measures should be designed to anticipate and prevent threats, rather than simply reacting to them”.2 The PWG’s initial approach was a clear example of being caught in the “current fight” at the expense of long-term security.

The updated PWG structure—centered on a 72–96-hour planning window—marked a significant improvement. Its outputs are now oriented toward informing tactical decisions and enabling proactive security measures. These outputs should include recommendations to the Deputy Commanding General–Support (DCG-S) for changes to the PPL; TWG nominations for targets beyond +72 hours; force protection condition (FPCON) change recommendations; updated threat assessments; identification of risks and vulnerabilities; recommendations for protection equipment and technology distribution; proposed task-organization changes; responses to variances in plans; and fragmentary order (FRAGO) inputs for execution beyond +72 hours.

A successful PWG relies on high-quality information drawn from a wide range of sources. To produce effective long-range plans, it requires robust input from nearly every staff section as well as from subordinate units. This comprehensive input enables the staff to collaborate effectively and focus on where the division needs to be 72 to 96 hours in the future, rather than on its current position.

During WFX 25-3, nearly every staff section contributed to the PWG: FUOPs (G-35) provided planning horizons out to +96 hours; the Division Engineer (DIVENG) assessed critical equipment and survivability; the Medical Officer (MEDO) supplied force health protection trends; the G-4 reported route status and critical logistics pushes beyond +72 hours; Air and Missile Defense (AMD) assessed air defense effectiveness; chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN), provost marshal office (PMO), and explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) provided troop-to-task updates; space, cyber electromagnetic activities (CEMA), and IO sections contributed nonkinetic effectiveness assessments and nominations beyond +72 hours; and major subordinate commands (MSCs) provided essential ground truth through their Brigade Protection Working Groups (BPWGs). This breadth of inputs allowed the staff to collaborate more effectively and maintain a forward-looking focus on where the division will be beyond the 72-hour mark.

The resulting improved collaboration enabled the staff to make better-informed decisions about adjusting priorities within the PPL’s tiered system. Because these decisions were based on FUOPs, subordinate commands gained the lead time necessary to plan and execute their protection efforts effectively. This framework ensures that, by the time an order is issued, the units responsible have had sufficient time to prepare and posture their forces accordingly.

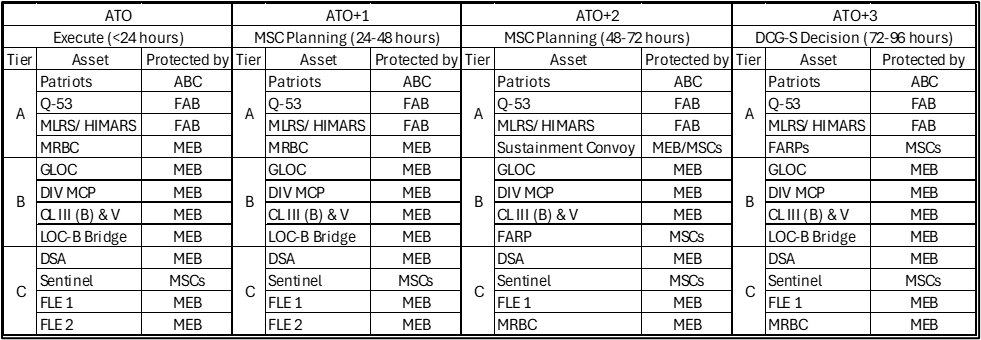

To simplify this for the Commanding General (CG), the daily protection update included a chart (see Figure 3) that offered an at-a-glance summary of the protection plan. The chart identified which subordinate command was responsible for each key asset and visually depicted the planning cycle.

Figure 3: 42nd ID Protection PPL Running Estimate

The Role of Protection and the Targeting Decision Cycle

A key output of the PWG, as previously discussed, was the development of nominations for the TWG. In practice, the PWG helped identify potential threats and recommend appropriate actions to address them. During WFX 25-3, the 42nd ID protection specialists reinforced this approach by prioritizing the security of FUOPs and planning more than 72 hours in advance.

A critical improvement was the inclusion of FUOPs planners (G-35) in PWG meetings. Their insight into upcoming missions allowed the group to develop a more effective protection plan, incorporating both lethal and nonlethal measures for nomination in the TWG. For example, in preparing for the WFX (+72 hours), the cell conducted a detailed review of the protection plan and proactively addressed potential vulnerabilities. This enabled the team to better integrate nonlethal effects and generate more effective target nominations for the TWG. By establishing clear PWG outputs that directly informed other working groups, the division strengthened staff coordination and enhanced planning across the protection warfighting function.

The Role of Intelligence and Proactive Reprioritization

A key lesson from WFX 25-3 was the need for the intelligence officer (G-2) within the PWG to shift focus. Rather than limiting their input to current enemy activity, the G-2 must anticipate how the enemy is likely to react to friendly plans 72 to 96 hours into the future. This forward-looking approach aligns directly with ADP 3-37’s emphasis on understanding the adversary and anticipating their actions.

The purpose of this analysis is to enable proactive defense. It allows the protection team to shift its priorities and allocate defensive resources based on anticipated threats. By identifying enemy patterns, the division can position its defenses to counter the enemy's likely next move. This proactive stance gives subordinate commanders the time they need to plan and prepare—far preferable to reacting under the pressure of emerging crises.

Conclusion

WFX 25-3 underscored a critical lesson: effective protection requires proactive planning, not merely reacting to immediate threats. Early in the exercise, the division struggled because it remained trapped in a cycle of responding to enemy actions rather than shaping future conditions.

To break this cycle and improve overall effectiveness, protection teams should adopt three key changes:

- Extend the Planning Horizon: Shift from short-term reactions to planning at least 96 hours in advance.

- Integrate with Other Teams: Work closely with other planning groups—especially FUOPs (G-35) and the TWG—to ensure that protection considerations are embedded into every plan.

- Use Predictive Intelligence: Refocus intelligence (G-2) efforts from reporting current enemy activity to anticipating how the enemy will respond to FUOPs.

The bottom line is that by adopting these changes, divisions can better anticipate and neutralize threats, improve their resilience, and maintain battlefield superiority. The purpose of a protection cell is not merely to respond to danger—it is to anticipate it, shape the environment, minimize risk, and ensure mission success.

Endnotes:

1.U.S. Army, Army Doctrine Publication (ADP) 3-37: Protection (Washington, DC: Headquarters, Department of the Army, 2023), 2-2.

2.Ibid. 3-3

Captain Gulliford served as the Executive Aide to the Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear School Commandant. She holds a bachelor’s degree in music education from Jacksonville State University, Jacksonville, Alabama, and a master’s degree in curriculum and instruction from Averett University, Danville, Virginia.