Published 9/11/2025

Lieutenant Colonel Bryan B. Ault and Lieutenant Colonel Douglas D. Bazil

Introduction—The Operating Environment

In 7 Seconds to Die, Colonel John Antal (Retired) recounts the harrowing experience of Armenian soldiers facing loitering munitions. He describes, “When Armenian soldiers spotted or heard the Harop [loitering munition,] they knew they had seven seconds to take cover before it struck. One Armenian soldier stated: ‘There was no place to hide and no way to fight back.’”1

The current operating environment is defined by persistent ground and overhead sensors linked to precision fires, making every asset observable, targetable, and destroyable. Despite having observed the lessons of the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war and the ongoing war in Ukraine, the U.S. Army remains unprepared to protect Soldiers and critical assets in modern combat. Specifically, the Army has limited tactical air and missile defense, has no effective counter-unmanned aerial system (C-UAS) capability, has no standards for emissions control, and has failed to integrate the protection warfighting function at division and below echelons.2

Soldiers and small units must become harder to find and harder to kill. The division must fully integrate and layer its limited protection resources to safeguard the most critical capabilities, assets, and activities. U.S. Army transformation for large-scale combat operations (LSCO) should incorporate changes to our doctrine, organization, and materiel to increase survivability within divisions. U.S. Army divisions must prioritize force protection across all echelons—from individual Soldiers to the division level—leveraging every available asset to preserve combat power and ensure freedom of action. Divisions accomplish this by enforcing passive protection through camouflage, concealment, and dispersion; practicing signature management through emissions control; and integrating the protection function across the battle staff.

Section 1: Hard to Kill

As part of the guiding principles for Soldiers in the First Infantry Division (1ID), the Bro 8 outlines a warrior’s mindset focused on survival and discipline. One of its core tenets reads: “Hard to Kill: I will make it hard for the enemy to find me and kill me—I will practice noise, light, and electronic discipline. I will camouflage and improve my fighting position as though my life and those of my team depend upon it.”3

Protecting the force begins with fieldcraft and awareness. Soldiers face the threat of continuous observation. In addition to camouflage and concealment in the visible spectrum, Soldiers must conceal their thermal, acoustic, and electronic signatures. Soldiers must understand the importance of “looking up” and be able to employ C-UAS measures. Operational security (OPSEC) must be enforced at all echelons, including strict control over access to Microsoft® Teams (MS Teams), scrutiny of social media content, and careful review of articles discussing new unit capabilities. Soldiers must be aware that seemingly innocent posts about new unit capabilities can have severe consequences.

Protection efforts must extend from the individual Soldier to the division’s critical systems. Effective signature management ensures that enemy forces have difficulty detecting our key systems, and even when they do, these systems are even harder to identify. The division must understand its electromagnetic signature and make every effort to blend into the existing environment to hide in plain sight. During National Training Center (NTC) rotation 25-03, the 1ID enhanced survivability by actively managing its electromagnetic signature—testing new capabilities, controlling the timing of capability unmasking, and implementing new forward arming and refueling point (FARP) protection measures.

Operating with low electromagnetic signatures is essential. Army transport systems (such as the Joint Network Node, Command Post Node, and Trojan Fingerprint command posts) produce unique signals, increasing the likelihood of detection. Newer systems (such as Kymeta®, Starshield, and cellular-based transport) are less detectable by ground-based sensors. Using a hard-wired, fiber-optic connection instead of radio frequency emitters can prevent detection in the electromagnetic operating environment.

Decisions to unmask a capability (emitting, radiating, or firing) must be deliberate, followed by immediate survivability moves. Such actions trigger the enemy’s kill chain to locate, track, target, and engage our forces. Units must implement emissions control procedures to “go dark” (no observable transmissions), “go dim” (transmit at a lower signature), or “go bright” (intentionally unmask).4 Emissions control measures apply to command posts but also to other key capabilities, such as sustainment and fires.

During NTC 25-03, the 1ID Combined Aviation Brigade (CAB) kept their FARPs in “silent status,” hidden within a logistics area of a brigade combat team (BCT). On order, the FARPs moved to a “hot status,” conducted fueling operations, and then displaced. Similarly, the 1ID Division Artillery (DIVARTY) protected their rocket artillery by dispersing it in hide sites, moving to fire, and then moving to new hide sites. These actions enhanced survivability by obscuring the unique signatures of critical systems and ensuring that the enemy could not easily locate them after revealing their position.

By deliberately managing radar emissions and executing timely survivability actions, DIVARTY and 1CAB preserved combat power. By the end of the exercise, 1ID DIVARTY retained 4–6 counterfire radars and 38–43 rocket artillery systems. Likewise, 1CAB still operated their three FARPs without losing an aircraft during FARP operations.

Section 2: Integrating Protection at the Division Level

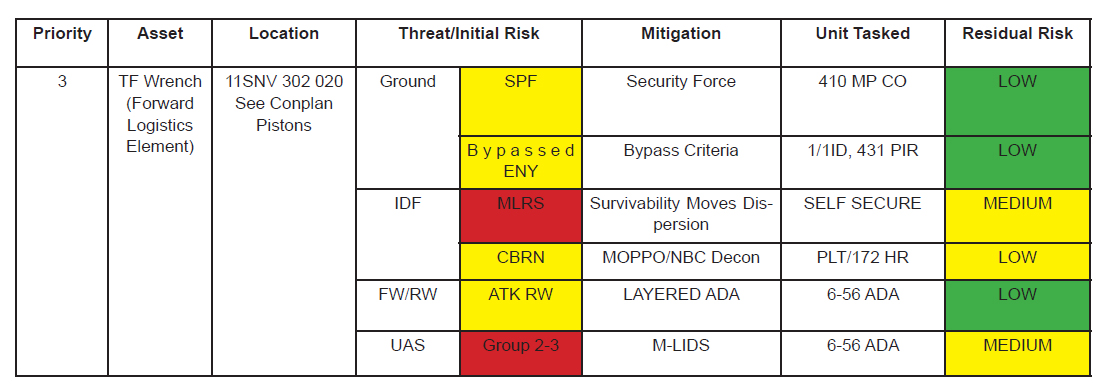

The division’s protection cell develops and maintains the Protection Prioritization List (PPL) during the military decision-making process (MDMP), continuously refining it throughout the operation. The PPL is often the reverse of the enemy’s High Payoff Target List. It outlines critical assets, operations, and activities against associated threats, vulnerabilities, and specific mitigation measures.7 Some assets remain on the PPL for the duration of the operation, while other assets are prioritized for specific phases. Changes to the PPL are made during midrange planning and typically require approval from the Commanding General or the Deputy Commanding General–Sustainment.

During planning a division counterattack at NTC 25-03, the division sustainment brigade commander identified that the destruction of the forward logistics element, Task Force Wrench, would cause the attack to culminate. Through the protection working group, the division placed Task Force Wrench as #3 on the PPL to safeguard this capability and allocated enablers to mitigate specific threats and vulnerabilities. This layered protection ensured the survivability of Task Force Wrench by reducing exposure to detection and targeting. A division cannot eliminate all risks, but it can make informed decisions to defend what is critical to mission success.

The PPL helps match protection capabilities to specific threats, reducing the risk to critical assets. (Source: 1ID Protection.)

Section 3: Recommendations for LSCO and Conclusion

U.S. Soldiers rehearse the use of a Dronebuster to engage enemy targets during Rotation 25-03. (U.S. Army Photo by Specialist Marques Martinez, Operations Group, National Training Center.)

To survive in future conflicts, U.S. Army divisions must fight to protect the force. From individual Soldiers to the division main command post, effective signature management is essential to make ourselves difficult to detect and hard to target. Traditional survivability methods will be ineffective against prolific sensors tied to precision fires. To adapt, divisions must fully integrate the protection warfighting function into the operations process, ensuring that limited resources are applied to protect the most critical assets.

1Antal, John F. 2022. 7 Seconds to Die. Casemate. 83.

2Judson, Jen. 2024. US Army’s Short-Range Air Defense Efforts Face Review Board. Defense News. https://www.defensenews.com/land/2024/02/22/us-armys-short-range-air-defense-efforts-face-review-board/

3Major General Rone, M. L., (2025). BRO 8: NTC training objectives. Unpublished document.

4Lieutenant Colonel T.R. Blair, interview by author. Phone interview, 4 February 2025.

5Brigadier General Mcbride, D.M., Personal communication, February, 2025.

6U.S. Army. 2024. ADP 3-37 (Protection), 3-12.

7U.S. Army. 2024. ADP 3-37 (Protection), 3-8 – 3-10.

8Tetreau, Matthew. 2023. Convergence and Emission Control. Military Review. https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Journals/Military-Review/English-Edition-Archives/November-December-2023/Convergence-and-Emission-Control/

9U.S. Army. 2024. ADP 3-37 (Protection), 4-3 – 4-4.

Lieutenant Colonel Bazil serves as the 1ID Provost Marshal. He holds a bachelor’s degree from Illinois State University, Normal, and a master’s degree from Webster University, Webster Groves, Missouri.