By Captain Carlos J. Valencia

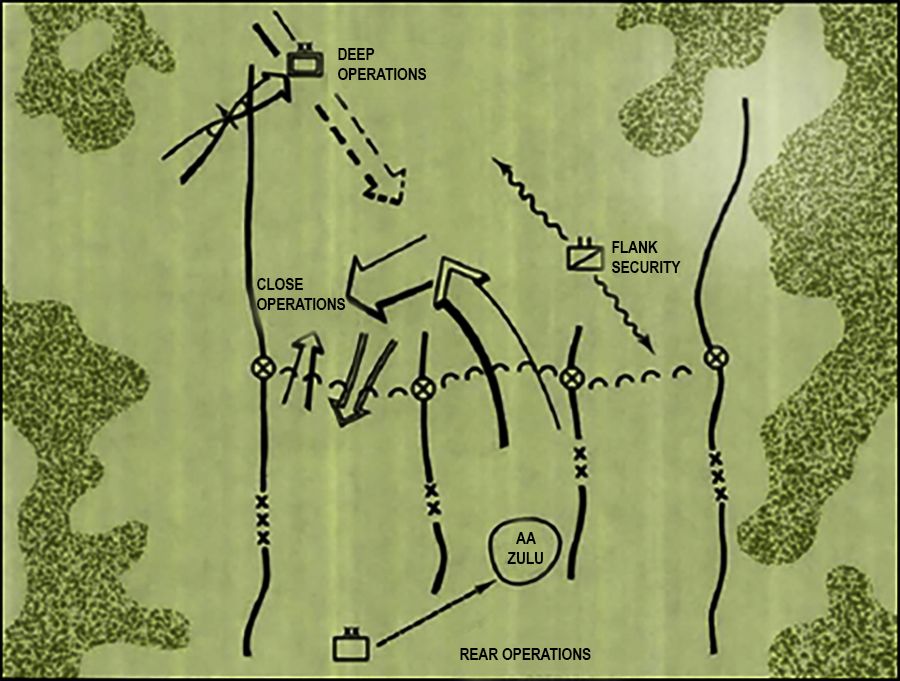

After a nearly 20-year focus on counterinsurgency/limited-contingency operations, the U.S. Army shifted its doctrinal focus back to large-scale combat operations in 2017. In October 2022, Field Manual (FM) 3-0, Operations,1 introduced the Army’s newest operation concept—multidomain operations, which includes many new elements such as the strategic context, the five domains/three dimensions of the operational environment, updates to the operational framework, and more. However, not all of the multidomain operations concepts are genuinely new. In August 1982, now-obsolete FM 100-5, Operations,2 introduced the Army’s operational concept of AirLand battle, which adopted a nonlinear view of the battlefield and was established to fight our enemies (the Soviets) through their depth with fire and maneuver, broadly expanding the battlefield and emphasizing unified air and ground operations. AirLand battle era doctrine introduced the elements of zones and sectors, main efforts, supporting efforts, and reserves; focused on the division as the unit of action; and included other doctrinal principles reintroduced as part of the multidomain operations concept. (See Figure 1 for a sample illustration of the operational framework [offense] during the AirLand battle era.) Even earlier versions of Army operational doctrine also shared concepts with or influenced present-day Army operational doctrine. For example, the 1962 version of FM 100-5, Operations,4 introduced the spectrum of war (encompassing the full range of conflict from cold war, to limited war, to general war), which is similar to the current strategic context (including competition below armed conflict, crisis, and armed conflict).

Doctrine is a living entity that builds upon itself; as adversaries change, doctrine must also change. In the process, professional knowledge is sometimes lost when it is no longer anticipated to be needed; however, obsolete doctrine can come to the rescue when necessary—as long as it can be found.

Legend: AA—assembly area

Figure 1. Example of the operational framework (offense) during the AirLand battle era3

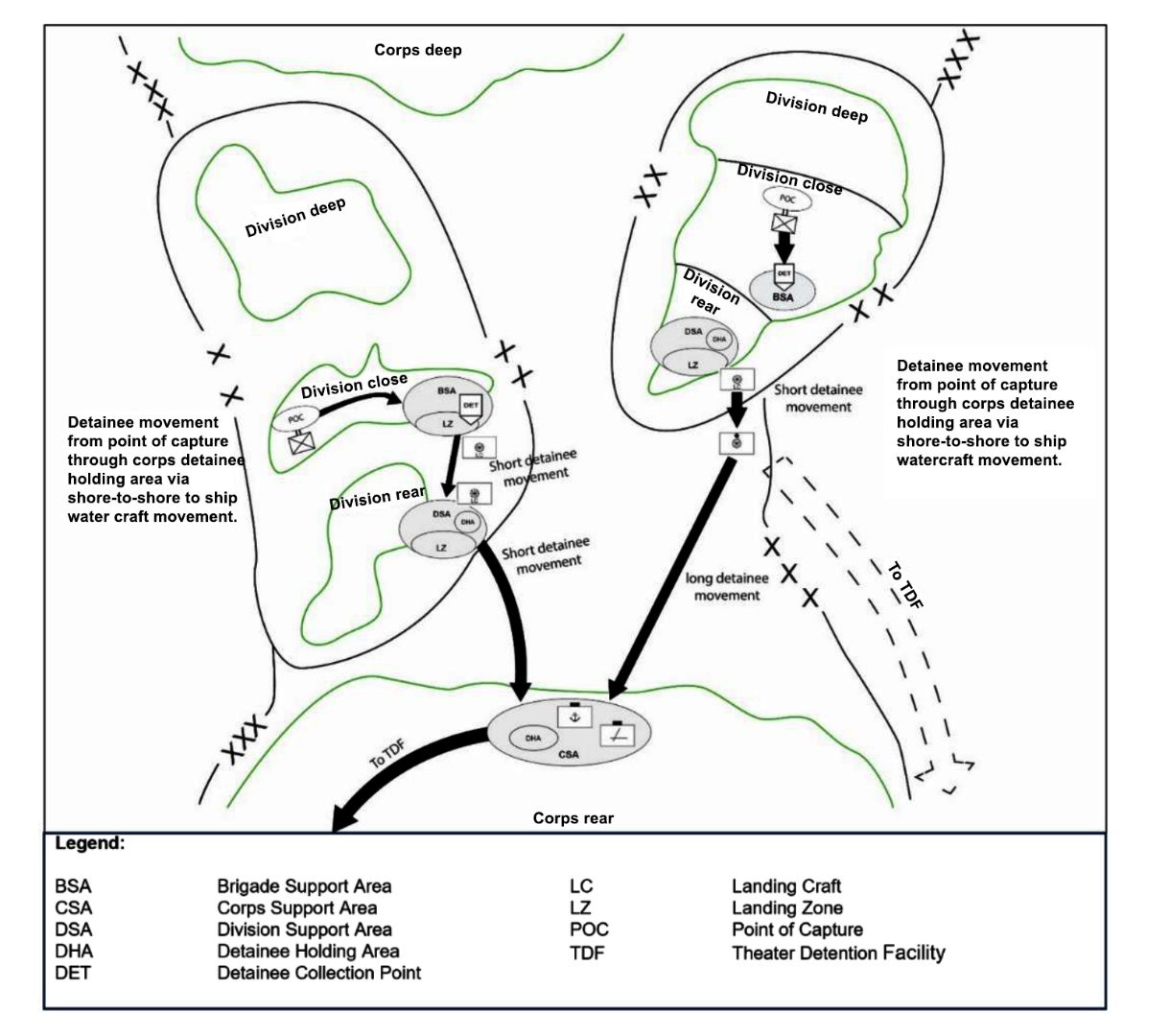

The basic disciplines and mission set of military police have remained relatively unchanged since the official birth of the Military Police Regiment in September 1941. Still, as military police, we have forgotten a thing or two as the face of warfare and technology has changed. A few months after I began working in the Military Police Doctrine Branch, Doctrine Division, Fielded Force Integration Directorate, Maneuver Support Center of Excellence (MSCoE), Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, our team received feedback from the field regarding a gap in our detainee operations doctrine. A group of observer coach/trainers overseeing an exercise in Hawaii had determined that FM 3-63, Detainee Operations,5 lacked sufficient information regarding the use of Army watercraft for transporting detainees. During the training, the observer coach/trainers and the unit they were supporting developed tactics, techniques, and procedures to bridge the gap and they submitted their findings to us. Following additional research on sister Service watercraft and detention doctrine, we developed actionable information that will be added to the next revision of FM 3-63 (currently under development)—but this was just the beginning. Over the next year, our team received additional feedback from the field regarding a need for more doctrinal information about detainee operations in maritime-dominated environments. We needed to determine the detainee operations framework for a maritime environment—an operational environment in which our enemy potentially has antiaccess/aerial denial capabilities. We arrived at boats as a solution, but things would get more complicated (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Maritime detainee framework

As outlined in Chapter 7 of FM 3-0,6 the operational framework in a maritime-dominated environment can be very different from that of a land-dominated environment since the rear, close, and deep areas can be located on different land masses. These noncontiguous areas of operations can create problems when transporting detainees from detainee collection points to a theater detention facility, as the normal detainee backhaul framework relies primarily on returning supply trucks. The simple solution to this issue would be to task Army or U.S. Navy watercraft to move detainees from land mass to land mass, but what if the distances between land masses are great? Army Techniques Publication (ATP) 4-15, Army Watercraft Operations,7 indicates that combat-equipped Soldiers should only be transported on the weather deck of a vessel for up to an hour, so how could a detainee movement of several hours or even several days be planned? Weirdly enough, we discovered that the Army seemed to be the first military Service contemplating large-scale detainee operations at sea. Current Navy and U.S. Coast Guard doctrine focuses mainly on the detention of pirates or migrants; this led us to think about history. We researched various island-hopping campaigns in the Pacific during World War II and learned that prisoners of war were moved from division/corps holding areas located across the ocean to detention facilities primarily in Australia, New Zealand and, occasionally, the mainland United States.8 We had a new starting point; but unfortunately, old Navy doctrine is hard to come by. (Most professional writing about World War II prisoners of war is focused on European combatants.) Still, we found what we were looking for on a bookshelf in the Doctrine Division at MSCoE—a dusty copy of now-obsolete FM 19-40, Handling Prisoners of War,9 with a section labeled “Evacuation by Water.” Following a few modern-day modifications to this old doctrine, readers of the upcoming iteration of FM 3-63 can look forward to using 72-year-old planning considerations for planning and executing a multiday maritime detainee mission.

This was but one of many times that our team has located and consulted older doctrine during my time in the Doctrine Division. Following the publishing of Army Structure (ARSTRUC) Memorandum 2025–2029,10 we looked for and incorporated verbiage and various graphics from FM 19-10, Military Police Operations,11 into the next edition of ATP 3-39.10, Police Operations,12 due to their continued relevance for emerging law enforcement activities and today’s police operations. We also borrowed concepts from now-obsolete FM 19-1, Military Police Support for the AirLand Battle,13 and combined them with feedback from the field when developing tactics, techniques, and procedures for littoral, port, and watercraft security for next edition of ATP 3-39.30, Security and Mobility Support.14 These are just a few examples of how our team has reinvigorated older or obsolete doctrine for use in upcoming publications as the Army focuses on large-scale combat operations. I envision more principles and concepts from the AirLand battle era and earlier being reintroduced and expanded upon.

If—after becoming entirely comfortable with the new version of FM 3-0 (published in October 2022)15—you have time, you could read the 15 previous editions of FM 3-0 and FM 100-5 and observe the evolution of the Army’s operational doctrine. But to save time, I will tell you that it is quite interesting to see how the Army shifts its focus back and forth between general conflict/large-scale combat operations (as in World War II, the Korean War, the Cold War, and conflicts of today) and insurgency/limited contingency-focused operations (as in the Vietnam War, the post-Cold War, and the War on Terror). Additionally, I will say that the readability of the series has improved over time, as doctrine developers have slowly omitted tactics, techniques, and procedures (on local security, troop movement procedures), which are better suited for other types of publications (such as today’s ATPs), and have streamlined and focused the series on operational-level topics and discussion. Overall, it’s fascinating to see how various concepts originated, disappeared, and reemerged. Although “obsolete” Army doctrine was genuinely a product of its time, it still retains significant value for military arts and sciences practitioners.

Army Doctrine Publication (ADP) 1-01, Doctrine Primer,16 defines Army doctrine as the “fundamental principles, with supporting [tactics, techniques, and procedures] and terms and symbols, used for the conduct of operations and as a guide for actions of operating forces and elements of the institutional force that directly support operations in support of national objectives”; I define it for the Military Police Captains Career Course as “all the language and lessons learned from the Army’s 270-plus years of warfighting.” As I have studied, reviewed, written— and, basically become immersed in—doctrine for the past 2.5 years, I have seen my definition become more and more accurate. Doctrine is genuinely a living entity, and understanding it is imperative for success in all operations. However, doctrine is descriptive—not prescriptive. It provides leaders with a “50 percent plan”; it’s up to leaders to develop the other 50 percent.

Endnotes:

1FM 3-0, Operations, 1 October 2022.

2FM 100-5, Operations, 20 August 1982 (now obsolete).

3Ibid.

4FM 100-5, Operations,19 February 1962 (now obsolete).

5FM 3-63, Detainee Operations, 2 January 2020.

6FM 3-0. 7ATP 4-15, Army Watercraft Operations, 3 April 2015.

7ATP 4-15, Army Watercraft Operations, 3 April 2015.

8Arnold Kramer, “Japanese Prisoners of War in America,” Pacific Historical Review, 1983, pp. 67–91, <https://doi.org/10.2307/3639455>, accessed on 17 April 2024.

9FM 19-40, Handling Prisoners of War, 3 November 1952 (now obsolete).

10Army Structure (ARSTRUC) Memorandum 2025–2029, Department of the Army, 27 February 2024.

11FM 19-10, Military Police Operations, 30 September 1976 (now obsolete).

12ATP 3-39.10, Police Operations, 24 August 2021.

13FM 19-1, Military Police Support for the AirLand Battle, 23 May 1988 (now obsolete).

14ATP 3-39.30, Security and Mobility Support, 21 May 2020.

15FM 3-0.

16ADP 1-01, Doctrine Primer, 31 July 2019.

Captain Valencia is a doctrine analyst/writer for the Military Police Doctrine Branch, Doctrine Division, Fielded Force Integration Directorate, MSCoE. He holds a bachelor’s degree in history from the University of Texas, San Antonio.