![]()

Published 2024 By Colonel Richard S. Vanderlinden (Retired)

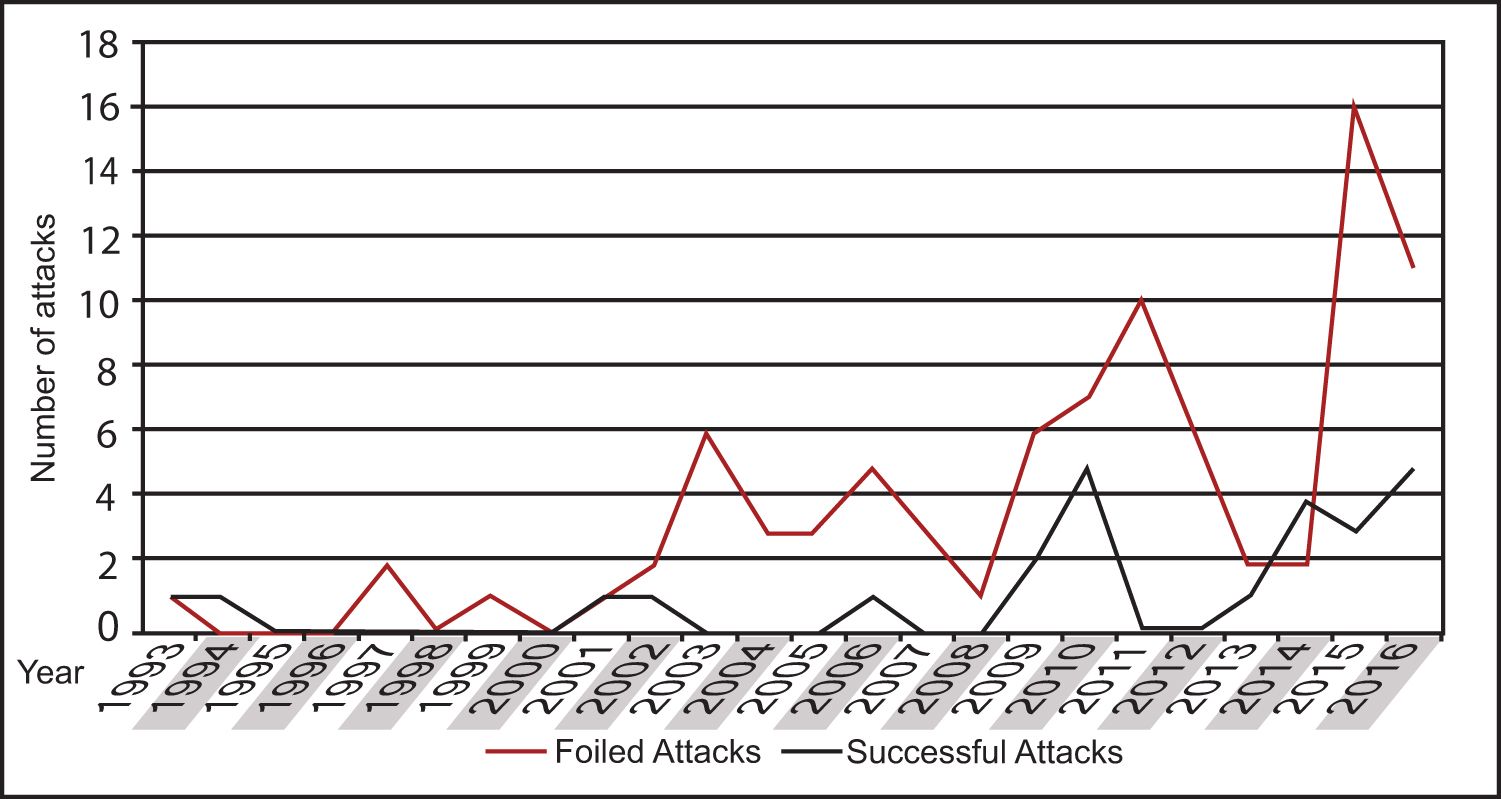

Despite the understandable shift in Department of Defense mission priorities and resources toward threats from near-peer competitors, the threat posed by terrorists and violent extremists has not diminished. Recent terror attacks, such as the 7 October 2023 Hamas attack on Israel and the 22 March 2024 Islamic State Khorasan Province attack in Russia, reveal the fact that large-scale terrorist attacks remain possible. Of equal concern, the Hamas and Islamic State Khorasan Province attacks demonstrate the ability of some groups to conduct external operations. A 2017 research brief by investigators for the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism highlights the volume of attempted jihadist attacks, including those thwarted by public and law enforcement efforts; according to the brief, since the February 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center in New York City, New York, there have been 121 jihadist-linked plots to use violence against the American homeland.1 The numbers of attempts and successful plots have increased in recent years (2003–2016) in the United States and other countries, with a steep increase after 2014 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Frequency of successful and foiled attacks by year (1993–2016)2

Antiterrorism Strategy Sets the Tone for Community Action

In February 2024, the U.S. Army Provost Marshal General approved Maneuvering the Phalanx: Army Antiterrorism Strategic Plan, Phase V–2023, which plots the way ahead for Army antiterrorism over the next several years.3 As with any strategy, it represents a projection based on the known past and the logical analysis of future developments. Although no plan can guarantee success, the Army Antiterrorism Strategic Plan prompts action aimed at achieving the vision of “preventing terrorism, protecting our people, and ensuring Army readiness.”4 The need to improve threat information sharing and suspicious-activity reporting is embodied in the vision and objectives of the plan. This is where strategic planning connects with local police community engagement to prevent terrorist and violent extremist activities. Numerous tasks contribute to terrorism prevention, but few are more important than individual awareness and the willingness to take action to protect one’s community.

Prevention Programs Contribute to Community Vigilance

The Army Protection Program includes many enabling functions that offer tools and techniques to help local police and communities ensure a safe and secure environment while also supporting warfighter readiness. The Army employs numerous prevention programs; the following programs are specifically linked to terrorism prevention:

- Crime prevention, defined as “efforts to reduce criminal opportunity, protect potential human victims, and prevent property loss by anticipating, recognizing, and appraising crime risk and initiating actions to remove or reduce it,”5 is one of the most enduring prevention programs within the Army, and it contributes to terrorism prevention. By preventing crimes of all types—including acts of violence such as terrorism—Army communities maintain a secure environment.

- Operations security is a primary task within the protection warfighting function. The primary purpose of operations security is to protect critical information that is vital to the successful achievement of unit objectives and missions while denying access to this information to our adversaries. Protecting critical information makes it more difficult for terrorists to gather intelligence during planning and target selection cycles.

- iWATCH Army was one of the first neighborhood watch initiatives focused on terrorism prevention. Developed in 2009 and modeled after the Los Angeles, California, Police Department iWATCH program, iWATCH Army encourages and empowers the Army community to identify and report suspicious behavior that might potentially be associated with terrorist activity. Individual situational awareness of one’s surroundings is a passive element of iWATCH Army. An active element of iWATCH Army involves individuals taking action to report suspicious behavior or activities to military police or local law enforcement agencies for investigation.

- iSALUTE is an Army counterintelligence reporting program. According to an “Antiterrorism Awareness— iSalute” article, “Unlike iWATCH Army, iSALUTE seeks to discover, prevent, and report espionage, sabotage, subversion, and international terrorism. iSALUTE seeks Army-wide community support to report threat incidents, suspicious activity, and counterintelligence matters that are potential indicators of espionage, terrorist-associated insider threat, and extremist activity.”6

- Insider threat refers to “a person with placement and access who intentionally causes loss or degradation of resources or capabilities or compromises the ability of an organization to accomplish its mission through espionage, providing support to international terrorism, or the unauthorized release or disclosure of information about the plans and intentions of U.S. military forces.”7 Examples of U.S. military insider threats include the 2009 terrorist mass shooting at Fort Hood, Texas; the 2013 Washington, D.C., Navy Yard shooting; and the 2010 leaking of classified information by Private Bradley E. Manning (now known as Private Chelsea E. Manning). In 2013, the Army established an insider threat program designed to prevent, deter, detect, and mitigate actions by insiders who represent a threat to national security. A key component of the insider threat program is training the workforce on indicators of possible insider threats and on reporting procedures.

- Joint Analytical Real-Time Virtual Information-Sharing System (JARVISS), a threat common operational picture and information-sharing platform for the antiterrorism and broader protection and warfighter communities, helps to identify and assess threat and hazard incidents, allows collaboration with internal and external stakeholders, and assists leaders in making informed decisions using advanced data analytics. The JARVISS program management team is in the process of fielding a JARVISS mobile application, which will expand the use of the platform and include a tool for users to report suspicious activity, threats, and incidents and to share information. JARVISS is currently capable of submitting eGuardian suspicious-activity reports into the eGuardian system and archiving the suspicious-activity reports information for data analytic purposes in the future.

- eGuardian is “a web-based platform where federal and state law enforcement entities can collaborate, coordinate, and deconflict investigative activity. eGuardian allows other federal agencies; state, local, tribal, and territorial law enforcement entities; the Department of Defense; and fusion centers to document, share, and track potential threats; suspicious-activity; and cyber, counterterrorism, counterintelligence, or criminal activity with the FBI [Federal Bureau of Investigation] and with each other.”8 The Army has been an avid participant in the eGuardian program from its inception in December 2008. Antiterrorism awareness emphasizes the importance of ensuring the involvement of the entire Army community, while eGuardian provides a means for the community to report suspicious activities. The Antiterrorism Division of the U.S. Army Office of the Provost Marshal General, Washington, D.C., produces antiterrorism awareness and suspicious-activity report informational materials to encourage the use of eGuardian. Reports of suspicious behavior or activity submitted to military police are reviewed through law enforcement and investigative channels and then routed through the U.S. Army Criminal Investigation Division for approval and entry into eGuardian. With capabilities that include email notification, a user dashboard, and custom searches, eGuardian allows users to be aware of when a relevant incident is available and to apply basic analytics. A geospatial mapping tool that can be used to map relevant incidents is also available. Military police organizations should contact local Criminal Investigation Division offices for eGuardian support.

- Don’t Be a Bystander is a prevention program that is based on the notion that bystanders are often best positioned to spot indicators of radicalization and mobilization toward violence—and often prior to law enforcement agency awareness or ability to investigate.9 When bystanders serve as active observers and report suspicious behavior or activity, they extend the eyes and ears of security and law enforcement agencies; therefore, it is vital that military police and local law enforcement agencies take active, positive measures to engage their communities and encourage assistance with community protection. Building relationships of trust and encouraging community members to remain vigilant to local threats can lead to bystander willingness to report suspicious behavior and activities. Each of these programs has its own characteristics and functions, and each plays a role in terrorism prevention. The linchpin that ties all of the prevention programs together in support of terrorism prevention is Army policing.

Conclusion

Effective community engagement is a key task for all law enforcement agencies. As former U.S. Attorney General William P. Barr once stated, “Serving as a police officer is the toughest job in our country. As they put themselves on the line to keep us safe, they deserve our gratitude and support.”10

Community policing is a “philosophy that promotes organizational strategies that support the systematic use of partnerships and problem-solving techniques to proactively address the immediate conditions that give rise to public safety issues such as crime, social disorder, and fear of crime.”11 According to Army Techniques Publication (ATP) 3-39.10, Police Operations, the foundation of community policing consists of effective and enduring “police operations and associated activities, which are critical to the commander’s antiterrorism program.”12 Army policing techniques are detailed in ATP 3-39.10, which includes extensive information on the role of military police in antiterrorism and community policing (including plans to prevent, defend against, and respond to terrorist activities). ATP 3-39.10 also mentions the community-based iWATCH Army program, and Chapter 7, “Police Engagement,” describes the planning, coordinating, and conducting of community engagements.

According to Anthony A. Braga’s article entitled “Crime and Policing Revisited,” “Developing close relationships with community members helps the police gather information about crime and disorder problems, understand the nature of these problems, and solve specific crimes.”13 Community-oriented policing can be a cornerstone for building community partnerships and—by helping to operationalize prevention programs—can support terrorism prevention. Community members who trust the police are more likely than those who do not to report suspicious behavior or activity that may be associated with terrorism or violent extremism. A whole-of-community approach to the prevention of all threats and hazards supports force protection and warfighter readiness.

Endnotes:

1Erik Dahl et al., “Comparing Failed, Foiled, Completed and Successful Terrorist Attacks,” National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and the Responses to Terrorism, December 2017, <https://www.start.umd.edu/research-projects/comparing-failed-foiled-completed-and-successful-terrorist

-attacks>

Colonel Vanderlinden (Retired) is a principal military analyst with the Antiterrorism Division, Office of the Provost Marshal General. He holds a bachelor’s degree in criminal justice from Northern Michigan University, Marquette, and master’s degrees in criminal justice from Michigan State University, Lansing, and strategic studies from the U.S. Army War College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania. He is also a graduate of the FBI National Academy.