The 1920s marked the true beginning of civilian aviation in the United States. By 1930 nearly 1700 civilian airports had been established in the nation. As part of this national trend, in 1927 the City of Savannah bought 900 acres of woods, pasture, and swamp three miles south of the city limits for the first Savannah Airport—later known as Hunter Field.

SAVANNAH AIRPORT

In three years, using mostly chain-gang labor, Chatham County ditched the area, graded the field with 400,000 cubic yards of sand, and planted it with Bermuda grass. The landing area was 4,500 feet long and 3,500 feet wide with no runways. Aircraft could take off and land in any direction. The original airfield lay roughly on what is now Hunter Army Airfield’s parking apron.

The first Savannah-based flying service, Strachan Skyways, moved into this hangar after it was built. Henry G. “Sandy” Strachan, a prominent local aviator of the 1930s, owned and managed the airport.

According to the Savannah Morning New, Strachan was “recognized as one of the leading fliers of Georgia… [and] credited as much as anyone else with bringing the magical world of flight to Savannah’s attention.” Air activity grew apace with the airfield. By decade’s end, the airfield hosted regular flights from both Delta and Eastern Airlines.

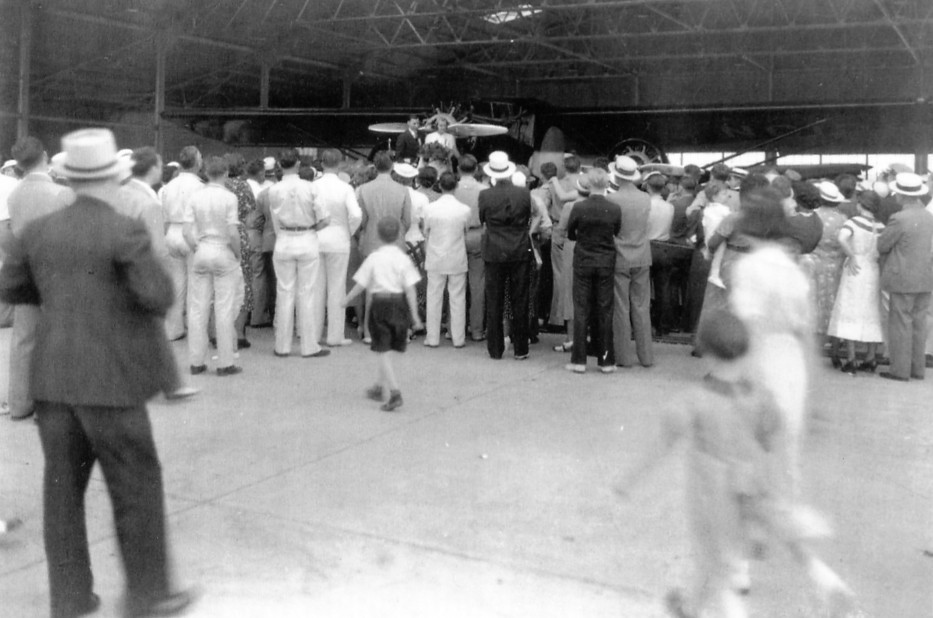

A crowd views a Strachan Skyways aircraft on display at the Savannah Municipal Airport hangar on February 13, 1937. From 1927 to 1949, before the War Department took it over, Hunter Army Airfield served as Savannah’s Municipal Airport. (Photo from the Cordray-Foltz Collection, courtesy Georgia Historical Society)

Jeanne Hunter, sister of “then” Col. Frank O’ Driscoll Hunter, unveils a plaque at the dedication ceremony of Hunter Field on May,19, 1940. Hunter Army Airfield was named after Hunter in 1940.

When Hitler invaded Poland in September 1939, the U.S. Army had 175,000 men, ranking 17th in the world—weaker than both the Dutch and Romanian armies. Meanwhile, the Japanese, locked in combat with the Chinese since 1937, were looking to expand their empire in Asia. The Air Corps, part of the Army at the time, had only 2,200 obsolete aircraft stationed at 24 airfields around the country. Europe and China were engulfed in war, and although the U.S. was not yet involved, in the corridors of Washington preparations began for a military build-up. Still, the war seemed far away from Savannah in that late summer. The Air Corps commissioned Sandy Strachan a lieutenant in September, but business continued as usual at the airport. In 1939-1940, the city built a permanent municipal airport building to house growing administrative activities of the airport. The building’s terrazzo floor previously on the flight line, is intact at the Mighty Eighth Air Force Museum in Pooler, Ga. On 19 May 1940, the city officially dedicated the airport as “Hunter Field.”

HUNTER FIELD GOES TO WAR

In 1940, the U.S. began to re-arm in preparation for war. The government increased funding for new equipment and bases and instituted a peace-time draft. A primary beneficiary of this new bounty was the Air Corps, which by 1941 had grown to over 25,000 personnel and 4,000 aircraft. The Air Corps needed new airbases to accommodate its growth, and in August 1940, selected Hunter Field as a light bomber training base.

Units trained at Hunter Field later saw active combat in all major theaters of war, including the China-Burma India Theater, the Pacific, and in Europe.

Over the past 60 years the installation has demolished most of its 450 World War II buildings. World War II structures that remain include a water tower, an abandoned ammunition storage area, a heat plant, two bomb sight storage facilities, the sewage treatment plant, the small arms range (used in World War II to test fire and sight in aircraft-mounted machineguns and cannon), three hangars and various administration buildings and warehouses.

Brig. Gen. James Fitzmaurice (a colonel at the time) stands with Savannah Mayor Thomas Gamble, examining a plane at the City of Savannah Airport in 1945. (Photo from the Jim Blaes Collection, courtesy Mighty Eighth Air Force Museum)

After Germany’s surrender in May 1945, Hunter Field processed aircraft and crew returning from the Mediterranean and slated for duty in the Pacific. This operation was cut short on 6 August 1945, when the B-29 Enola Gay, piloted by Colonel Paul Tibbetts, dropped a terrible new weapon—an atom bomb—on the Japanese city of Hiroshima, killing 100,000 Japanese. A second bomb dropped on Nagasaki prompted the Japanese government to surrender unconditionally. The mushroom clouds over Hiroshima and Nagasaki marked the final act of World War II and ushered in an era of global uncertainty. Would the destructive power of the bomb force an end to war? Or would the bomb lead to an end to humanity?

A MUNICIPAL AIRPORT AGAIN

After 1945, Hunter Field reverted to the Savannah Municipal Airport. The airport only used a small fraction of Hunter Field’s cantonment, the balance leased by the Federal Public Housing Administration to various public and private enterprises. Businessmen converted buildings to industrial plants, commercial businesses, and even apartments. The University of Georgia, overwhelmed with returning veterans, even opened a satellite campus on the old airbase.

THE COLD WAR AND STRATEGIC AIR COMMAND

As the 1940s ended, the Soviet Union, formerly a World War II ally, showed itself under the dictator Josef Stalin, to be an implacable foe of western capitalism and democracy. The Soviets took control of Eastern European nations, attempted a blockade of Berlin in 1948, and exploded their own atomic weapon in 1949. The U.S. grew increasingly concerned with Communist aggression and expansion. In 1947, President Truman signed the National Security Act (NSA), reorganizing the U.S. defense and intelligence establishments and making the Air Force a completely independent branch of service. Because of its role in atomic bomb deployment, the Air Force became the most important branch of the service. The Air Force’s Strategic Air Command (SAC) was responsible for atomic bomb delivery, making it the most important of the Air Force commands.

SAC accepted and in September 1950, the switch occurred. Hunter Field became Hunter Air Force Base (Hunter AFB), while Chatham Field became the Savannah Municipal Airport, now known as the Savannah/Hilton Head International Airport.

Hunter Air Force Base’s old air terminal and air traffic control tower circa 1951.

In June 1950, Communist North Korea invaded South Korea, starting the Korean War (1950-1953). Concerned that this attack was orchestrated by Moscow as the first round of World War III, the Truman administration began an immense American military build-up, with SAC a major beneficiary. During the Korean War, the U.S. nuclear arsenal increased from 300 atomic bombs to over 800, while SAC grew from 59,000 to 153,000 personnel, developed and issued new jet aircraft, and built up new bases, including Hunter AFB.

THE NEW LOOK

In 1952, Dwight D. Eisenhower was elected President. After Eisenhower’s election, a series of military and political events, including the development of thermonuclear weapons thousands of times more powerful then atomic bombs, spurred the arms race between the US and the Soviet Union. It was thus under Eisenhower that the concept of deterrence through the threat of massive nuclear retaliation became central to US strategic planning, and was formalized in a reform of the military establishment called “The New Look”—named after a style of women’s fashion advertised in Vogue magazine. Under the New Look, the Eisenhower administration stressed the deterrent potential of nuclear weapons by making SAC the centerpiece of the military establishment, and from 1953 to 1961 SAC received nearly 50 percent of the entire U.S. military budget.

With this massive increase in funding, it is no surprise that many buildings at Hunter Field today date from this time period.

From 1953 to 1956, the installation, in conjunction with the Savannah District Corps of Engineers, constructed on-post Family housing, three massive pinwheel barracks, new double cantilever hangars, new administration and shop buildings, new air traffic control buildings, and new community and recreation facilities.

Throughout the previous year, in addition to undertaking regular duties, SAC personnel at Hunter AFB had been training to fly and maintain this new aircraft, vastly different from their World War II-vintage propeller-driven bombers. With its swept-wing design and bubble cockpit, it looked and maneuvered more like a fighter than a bomber.

In support of the combat crews, SAC maintenance personnel worked on aircraft along the massive concrete aircraft parking apron, capable of parking over 130 bombers and refueling tankers. The 2nd Bomb Wing operated from the north edge of the apron, while the 308th operated on the east edge. Basic maintenance and inspections of aircraft by combat squadrons and organizational/ periodic maintenance squadrons occurred in nose docks, or on the flight line.

FROM WING ROTATION TO REFLEX

In 1954, SAC headquarters rated the entire 38th Air Division combat-ready and nuclear-capable. The 38th took part in wing rotation, a SAC program bringing bombers within easy range of the Soviet Union through ninety-day tours at SAC bases in the United Kingdom and North Africa.

By 1956, SAC had developed a one-third ground alert concept, which envisioned a third of SAC aircraft on alert and armed, ready to take off within 15 minutes’ warning for retaliatory nuclear strikes. In 1956, SAC headquarters designated Hunter AFB as the first test site for this concept. Under Operation TRY OUT (November 1956-April 1957), Hunter AFB locked the installation down, placed a third of its aircraft in full alert configuration, and continued normal training and maintenance schedules. The next six months were a grueling ordeal for the officers and men at Hunter AFB. One airman of the 2nd Field Maintenance Squadron recalled. Hunter AFB proved the one-third alert concept feasible and SAC quickly moved to implement the program after TRY OUT.

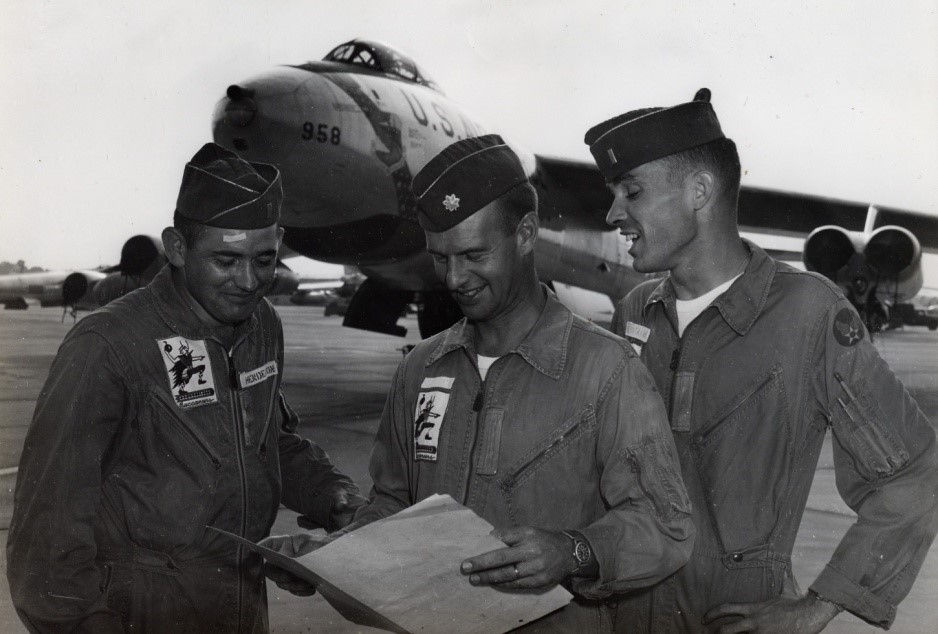

A B-47 crew of the 2nd Bomb Wing, based at Hunter Air Force Base review a flight plan prior to a flight in 1957. From 1950 to 1967, Hunter Army Airfield was referred to as Hunter Air Force Base and served under the Air Force’s Strategic Air Command.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, when the US faced the threat of missile attack with only a bomber force, one third ground alert remained critical to US nuclear deterrence, and SAC bombers used variations of this alert concept through the end of the Cold War. In July 1957, SAC also began Reflex operations, which stationed bombers on ground alert in overseas bases primarily in North Africa and England. Reflex soon replaced wing rotation. By 1958, Hunter AFB began both home station alert and Reflex operations.

In October 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik I, the first man-made orbital satellite, leaping ahead of the U.S. in what came to be known as the “Space Race.” Sputnik proved Soviet intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) capability. With the United States’ own rockets and missiles under development, SAC’s bomber alert and Reflex program became more important then ever to the country’s defense against Soviet missile attack.

CHANGING STRATEGIES

“Then” Brig. Gen. Hunter surrounded by several Army Air Corps officers in England. In the back row is also a Royal Air Force officer. Seated on Hunter's right is Her Majesty Queen Mary, wife of George VI, King of England. On the bottom of the paper on which the photo is fastened, is Mary's signature. In addition to the photos is the original notation written by Hunter that reads "Queen Mary and group of RAF and American officers at RAF station in England, 1943.

In the mid-1950s, SAC began basing bomb wings in the northern tier of the country, closer to the Soviet Union when flying over the Arctic Circle, and away from heavily populated areas. By 1955, the first B-52 heavy bombers—with greater range and payload capacity than the B-47—came online, while the U.S. deployed ICBMs by 1959. The development of ICBMs and the B-52 precluded the need for B-47 bases in the southeast. Hunter AFB became obsolete.

By 1960 SAC had transferred the 30th from Hunter AFB and announced the base’s eminent transfer to Material Air Transport Service (MATS), another Air Force command. Because of changes in technology and American nuclear strategy, Hunter AFB’s days as a SAC installation were definitely numbered.

MATERIEL AIR TRANSPORT SERVICE

Within six months of the end of the Cuban Missile Crisis, all SAC aircraft had left Hunter AFB. In April 1963, SAC transferred Hunter AFB to the 63rd Troop Carrier Wing of MATS (Materiel Air Transport Service), which stationed 60 C-124 cargo planes and 4,300 men to the installation. By 1964, tenant units had also moved to the base, including the Coast Guard. The 63rd’s missions were truly global, and flew in support of humanitarian efforts, the Gemini NASA missions, and military operations such as the U.S intervention in the Dominican Republic in 1965.

From left to right, B-25 Mitchell, Bell XP-77, Douglas A-20 and Beech C-45 parked on the Hunter Air Force Base flight line during WWII.

Significantly, missions to Vietnam gradually increased as the decade wore on and the U.S. became more deeply involved in that country’s affairs. In 1964, a year after MATS arrived, the Department of Defense announced Hunter AFB’s closing. Built as a SAC base, Hunter AFB did not have the facilities needed to support transport missions.

VIETNAM AND THE ARMY’S ARRIVAL

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Army developed troop-carrying transport helicopters, helicopter gunships designed for close air support, and tactical doctrine for airmobile warfare. These efforts paid off in a tactical sense when the U.S became involved in the Vietnam War. In 1965, U.S. combat troops were sent to bolster a shaky authoritarian regime in South Vietnam against an insurgency sponsored by Communist North Vietnam. The helicopter became the crux of the Army’s tactical efforts, essential in jungle terrain for air transport, fire support, medical evacuation, and supply.

A B-50 of the 2nd Bomb Wing undergoes maintenance at a nose dock on Hunter Air Force Base’s flight line, circa 1951.

HUNTER ARMY AIRFIELD: 1974 TO 2001

The Army reopened Hunter in 1974 and designated it a sub-post of Fort Stewart and a base for the 24th Infantry Division’s helicopter and support elements. In 1978, the 1st Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment moved to Hunter as a tenant unit.

CONFRONTING GLOBAL JIHAD: 2001 TO 2003

After a close and controversial election, in 2001 President George W. Bush was sworn into office. On September 11 of that year, al-Qaeda terrorists flew three passenger aircraft into the Pentagon and World Trade Center towers, killing 3,000 people. Once again, America was at war, although not with a traditional enemy, but an extremist religious movement.

The current protracted guerrilla conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq—fought as part of the larger War on Terror—have accelerated changes in organization and doctrine and also increased the construction tempo on Army installations, including Hunter. The Stewart/Hunter complex is the largest Army installation east of the Mississippi. It plays a vital role in the defense of this nation and continues to carry out difficult and dangerous missions in support of the rising democracy in Iraq and Afghanistan after this nation was attacked on a terrible September morning nearly eight years ago.

President George W. Bush, and wife Laura, arrive at Hunter Army Airfield in 2004 to attend the G-8 World Summit at Sea Island, GA. June 6-10.

Hunter remains an important deployment and support base for the Army and for other joint services, thanks to its existing airfield facilities and location adjacent to Fort Stewart and the east coast ports of Savannah and Charleston. In January 2003, Soldiers in the 3rd Infantry Division (Mechanized) were the first U.S. unit to enter Baghdad for Operation Iraqi Freedom during the invasion, and the first division to serve three tours in Iraq. The entire division deployed from Hunter Army Airfield to Kuwait in the weeks that followed. The 3rd ID spearheaded Coalition forces, fighting its way to Baghdad in early April, leading to the end of the Saddam Hussein regime. After combat, Soldiers from 3rd ID shifted focus to support and stabilization operations in an effort to rebuild the war-ravaged country. The division returned to Ft. Stewart in August 2003.

The Third Infantry Division was the first division in the U.S. Army to serve a second tour in Iraq. In January 2005, the division returned to Iraq and led U.S. and coalition forces in Baghdad. The hard work created conditions for a secure Iraqi election and transfer of power to the first democratically elected national government in the country. The Division served with its coalition partners during Operation Iraqi Freedom III for a year before returning to Fort Stewart-Hunter Army Airfield in January 2006. On November 17, 2006, the Army announced that the 3rd ID would be the first Army division to serve three tours in Iraq as part of the 2007 "troop surge." The Division Headquarters deployed from Fort Stewart through Hunter Army Airfield in March of 2007.

Task Force Marne was composed of more than 20,000 U.S. Soldiers, more than 26,000 Iraqi army soldiers, and over 46,000 Iraqi police. Along with combat operations, Task Force Marne focused on rebuilding the local government, Iraqi security forces and the economy. In the fall 2009, 3rd ID Headquarters, 2nd Brigade Combat Team and 3rd Brigade Combat Team deployed to Iraq for their fourth tour in that country while other units followed.

The majority of Soldiers from the 3rd Combat Aviation Brigade, based out of Hunter Army Airfield, began arriving in Afghanistan in support of Operation Enduring Freedom late in the summer of 2009. The 3rd CAB is a 3rd ID brigade but falls under the 82nd Airborne Division's operations in and around Regional Command East.

The 3rd CAB is organized by four multifunctional task forces comprised of UH-60 Blackhawk helicopters and MEDEVAC helicopters, AH-64D Apache Longbow attack helicopters, CH-47D Chinook helicopters, and the OH-58 Kiowa Warriors. In addition the 3rd CAB benefits from the skills of their aviation support battalion and an integrated reserve component from Texas.

This deployment marks the brigade's fourth deployment since 2003 in support of an Era of Persistent Conflict. The brigade's previous deployments were during the initial invasion into Iraq in 2003, OIF III in 2005 and OIF V in 2007.

It’s been 60 years since the Air Corps developed Hunter into a military airfield. During the Cold War, the installation adapted to the military’s changing needs, serving first as a bomber and air transport base for the Air Force, then as an Army helicopter training base, and finally as a rapid deployment node and home for an infantry division’s aviation units, in addition to tenant units including U.S. Special Operations units, a U.S. Marine Corps Reserve unit, the U.S. Coast Guard’s Air Station Savannah, the Georgia Air and Army National Guard units, the 224th Military Intelligence Battalion, the 260th Quartermaster Battalion, Tuttle Army Health Clinic and the units of the U.S. Intelligence and Security Command.

The Global War on Terror has passed into history but, chances are, it won’t be this installation’s final chapter as overseas contingency operations continue.